Jelvin Jose, Research Intern, ICS

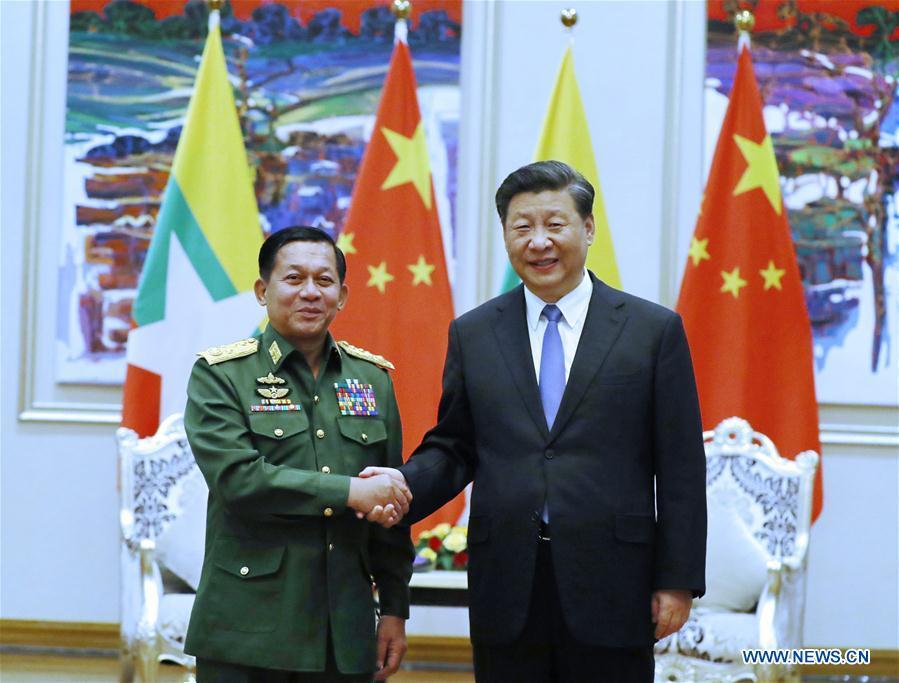

Source: China Daily

Seven months have passed since the Tatmadaw (Myanmar’s military) under General Min Aung Hlaing captured power in a military coup on 1 February 2021. China is one of the few major countries that did not condemn the coup. The Chinese response has continued to be carefully crafted to evade damaging its core strategic, security, and economic interests. Beijing’s official stance from the beginning has been that the coup is Myanmar’s internal affair, and the international community should refrain from “inappropriate intervention” while respecting Myanmar’s sovereignty.

Chinese Response to the Coup

Despite the widespread international opinion against the coup, Beijing and the Kremlin intervened to block the United Nations Security Council’s (UNSC) attempted move to condemn the coup in the immediate aftermath of its occurrence. In April, Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi communicated with several ASEAN leaders such as of Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines, and Singapore. Among the “Three Avoids” Wang emphasized to resolve the crisis were “inappropriate intervention by the United Nations Security Council,” undermining Myanmar’s sovereignty and external support to the popular unrest for “private gains” further stoking the crisis.

As per reports, the harsh language in a UNSC draft statement on Myanmar of March prepared by the U.K., including the direct reference to the coup and the threat of international action, was removed on the demands of China, Russia, India, and Vietnam. Similarly, on 18 June, China was among the 36 nations (including India and Russia) that abstained from voting on the UN General Assembly resolution against the overturn of Myanmar’s democratic government. The resolution was adopted by an overwhelming majority of 118 against one. In August 2021, the Chinese State Counselor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi participated in an ASEAN video conference pledging humanitarian assistance to Myanmar. While expressing concern over Myanmar’s overall situation and supporting ASEAN’s efforts to find a peaceful resolution to the crises, Wang, who carefully refrained from mentioning the coup, steadfastly maintained the position that this was ultimately Myanmar’s internal affair.

Decoding Chinese Response: Beijing’s Policy Imperatives in Myanmar

Over the years, Beijing has been the most prominent economic, political and military support pillar of Myanmar’s military junta when that regime has attracted international outrage and isolation. Nay Pyi Taw’s decades-long international isolation and sanctions, and the junta’s consequent reliance on China have largely helped Beijing carve out a dominant space in that country (along with other factors too, no doubt). Nevertheless, Beijing’s interests in backing the military had somewhat reduced since 2011, mainly after it found an alliance of greater convenience with Suu Kyi. After all, the military has traditionally harboured deep suspicion about Beijing’s intentions concerning Chinese support to various Armed Ethnic Organizations (EAO’s).

Nay Pyi Taw’s international isolation resulting from the military takeover is likely to help China reduce the strategic and economic competition it faces and diminish strategic, border security, and economic challenges it has recently encountered from Myanmar’s increasing international engagements, particularly with the Western countries and U.S. allies whom Beijing see as foes. However, while considering the overall scenario, Beijing does not view the present military takeover as unequivocally conducive to securing its interests in Myanmar and thus it is unhappy about the coup.

Two major reasons lead us to such a conclusion. First of all, “stability” is at the core of Chinese interests in Myanmar. Although the fall of democracy does not matter for Beijing, the unrest, chaos, and subsequent instability resulting from the coup gravely threaten Chinese economic interests. A peaceful, economically vibrant, and stable Myanmar is necessary to reap the benefits of the already huge Chinese investments in Myanmar, such as in the Kyaukpyu port project and Kyaukpyu special economic zone. More robust international investments and resultant economic gains would, predictably benefit the Chinese infrastructural and connectivity projects, even though, Beijing may not politically welcome investments from rivals such as Japan and India. In addition, the coup has also brought in the additional risk of alienating Myanmar’s civilian population as some popular sentiment has turned against Beijing for backing the military takeover.

Secondly, the coup does not provide any significant strategic or security advantages to Beijing but erodes them to some extent. Myanmar’s generals remain well aware of how crucial Beijing’s tacit support for them to remain in power. Thus, they may well try to please the Chinese leadership, by showing them the coup has not damaged Chinese interests in the country and that the military rulers remain highly accommodative of its interests. However, the present military leaders do not seem to be granting Beijing the degree of strategic and economic leeway in Myanmar that it had been receiving from previous military rulers. This is particularly true in the light of the fact that countries such as Japan, South Korea, and India have also remained unwilling to sever ties with Myanmar’s military regime.

Meanwhile, the continuing political instability and chaos in the country puts China’s border security – one of Beijing’s crucial objectives in Myanmar – at risk. China is wary of the prolonged political unrest in Myanmar as it fears that it would provide an excuse and opportunity for its rivals such as the U.S. and its allies to continuously interfere in Myanmar in a way that Beijing believes may risk China’s national security. This is of particular concern for the Chinese leadership considering China’s porous border with Myanmar in the Yunnan province.

Beijing knows very well that the Tatmadaw is a fiercely nationalistic organization, suspicious of China’s engagements and backing to the EAO’s, which the military sees as a peril to the country’s unity and integrity. Although the coup has increased Tatmadaw’s reliance on Beijing for tacit political and military support, which no other country except Russia is able to provide at the moment, Beijing is aware that the Tatmadaw will not hesitate to play Beijing against its other rivals like New Delhi or Tokyo if necessary. On the other hand, the partnership with the civilian government under Suu Kyi had, over time, become more convenient for Beijing than it had expected. Dealing with the civilian government also was helpful for Beijing to evade international criticism and image loss from backing the military.

Beijing equally looks forward to the return of a post-coup democratic mechanism if possible since the Chinese leadership also sees such an arrangement as more facilitating to the achievement of its interests. However, China’s tacit backing to the Tatmadaw leadership is aimed at damage limitation. Beijing does not want to sponsor democracy in the South East Asian country at its cost. Instead, China actively encourages ASEAN’s efforts to restore peace and democracy in Myanmar. Through this, Beijing intends to send a message that it is in support of Myanmar’s democratic transition. Moreover, Beijing, which views the U.S. and Western engagement with Myanmar as a threat, does not have such levels of threat perception regarding ASEAN. Altogether, China’s Myanmar policy today is guided by the sole mantra of best securing its own medium-term national interests.

The author is thankful to his mentor, Ambassador Vijay K. Nambiar, former Ambassador of India to China and UN Secretary General’s Special Advisor on Myanmar, for his invaluable guidance and support in writing this article. The views expressed here are those of the author(s), and not necessarily of the mentor or the Institute of Chinese Studies.