Rangoli Mitra, Research Assistant, ICS

Source: Reuters

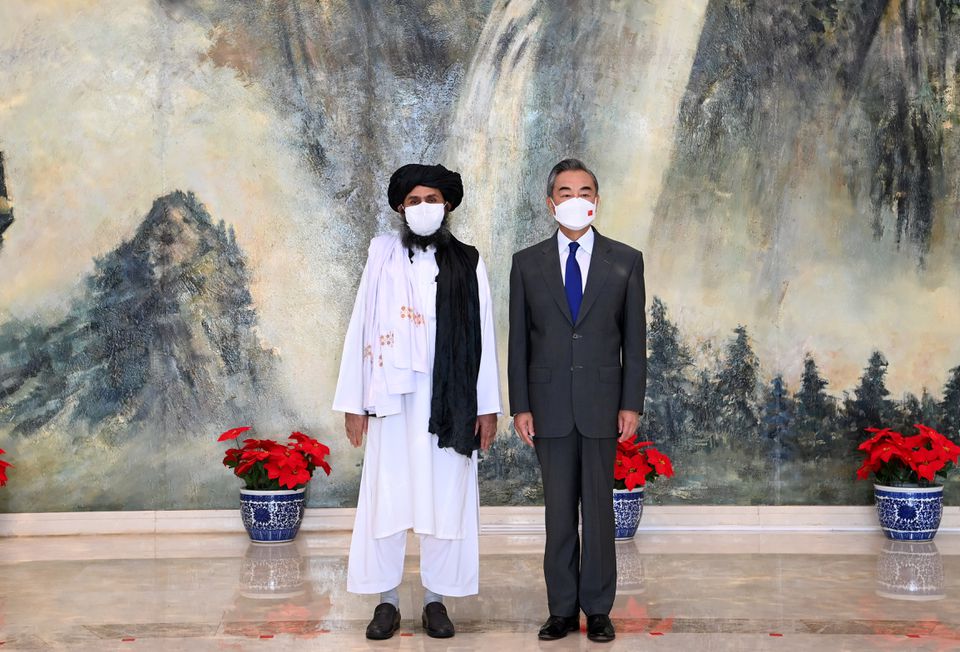

As America’s war in Afghanistan comes to a tragic end and the country experiences widespread chaos following the abrupt and complete collapse of the Afghan army and government in the face of the onrush of Taliban forces, China, an increasingly assertive power in the neighbourhood, appears to have chosen to deal with the emergent crisis in an unusually pro-active though precarious manner. Shortly after the fall of the entire country to the Taliban, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying told the media that the Chinese have noted that the Afghan war has come to an end and the Taliban have said that they will “negotiate the establishment of an open and inclusive Islamic government”. Working in tandem with its “all-weather” friend – Pakistan, China’s endorsement of the totalitarian Taliban government has sounded an alarm around the world, particularly, in the West; however, this is not entirely shocking as China seeks urgent political stability in Afghanistan.

China perceives the Taliban as more than just a religious extremist group and a real political force. Over the years, China was never convinced that the Taliban could be destroyed by military means, and in line with this strategic calculation, China had cautiously engaged with the group keeping future objectives in mind. Even though China has termed Afghanistan as the ‘graveyard of empires’ and never sought to entangle itself in the quagmire of the ‘great game’, it has been worried about the presence of the United States (US) on its Western border. As a ‘new great game’ begins, China has made its intentions clear- it will pursue a relationship with the Taliban for achieving its own ends. Thus, the central purpose of the present analysis is to explore China’s relation with the Taliban along with an attempt to understand the particular type of role China wants to play in Afghanistan.

A Historical Overview of China-Taliban Relations

Historically, Afghanistan was on the periphery of China’s diplomacy and China did not have a strong influence there. In 1993, one year after the Afghan communist regime collapsed, China evacuated its embassy amidst the violent struggle then taking place. China did not establish an official relationship with the Taliban who had seized power in 1996. However, it is interesting to note that efforts to establish a relationship with the Taliban dates back to 1999. In December 2000, China’s ambassador to Pakistan, Lu Shulin, even met the Taliban’s leader Mullah Omar in Kandahar. It is speculated that Mullah Omar assured the Chinese that the Taliban would not host anti-Chinese militants in Afghanistan. For the Chinese, threats emanating from Uighur militancy and the East Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM) have remained a primary security concern.

After it become clear that the US military surge in Afghanistan in 2010 would not defeat the Taliban, the Chinese gradually started developing ties with the group and seeking a greater role in the peace negotiations that were to follow. In 2015, China hosted secret talks between representatives of the Taliban and the Afghan government in Urumqi. The next year, a Taliban delegation headed by Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanekzai (then the group’s representative in Qatar) visited Beijing and sought the support of the Chinese for their position in Afghan domestic politics. As Chinese efforts intensified, the next high-level meeting was held in June 2019, when the group’s deputy leader Abdul Ghani Baradar visited China to discuss issues related to the Afghan peace process and counter-terrorism. In seeking a deeper relationship with the Taliban, China has inherently relied on Pakistan and Pakistani supporters of the Taliban, such as the late Maulana Sami ul Haq, known as the “Father of the Taliban”. In September 2019, when talks between the US and the Taliban faltered, China invited Baradar again to participate in an intra-Afghan conference in Beijing. However, this conference never took place. Apart from these unilateral initiatives, China was also a part of several multilateral initiatives such as the Quadrilateral Coordination Group and the Heart of Asia-Istanbul process.

The heightened significance of the Afghan war in China’s foreign policy is reflected in the fact that for the very first time China assigned a country-specific special envoy– since the creation of the post, there have been four Special Envoys for Afghan Affairs with the present being Yue Xiaoyong whose appointment on 21st July, 2021 comes at an extremely vital time.

Chinese Development Ambitions in Afghanistan

The highly publicized meeting of Taliban leaders (including Mullah Baradar) with the Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi in late July led to several crucial promises being made and Baradar even invited China to “play a bigger role in future reconstruction and economic development” of the nation.

Source: Stratfor

The unique geographical location of Afghanistan – as an important crossroad into Central Asia, Middle East and South Asia – makes it a primal factor in the success of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The importance of Afghanistan was noted by the former Chinese ambassador to Afghanistan Yao Jing who stated in 2016, “Without Afghan connectivity, there is no way to connect China with the rest of the world”. Up until the 16th century, Afghanistan played a pivotal role as a regional trade and transit hub sitting at the meeting point of ancient trade routes, known as the Silk Road. In 2011, a new initiative known as the New Silk Road was envisioned by the then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. However, this was later replaced by China’s BRI because the American initiative lacked the “Pacific-to-Atlantic scope”.

Afghanistan formally joined the BRI in 2016. Several projects such as the Five Nations Railway, Sino-Afghan Special Railway Transportation Project, Corridor 3 of the Afghan National Railway Plan and the Digital Silk Road, specifically the fiber optic link with China through Afghanistan’s Wakhan corridor, have been undertaken by China and the Afghan government. Afghanistan also became a member of the Asian Investment and Infrastructure Bank (AIIB) in October 2017 in order to facilitate cooperation on infrastructure development under the BRI and Regional Economic Cooperation Conference on Afghanistan (RECCA). In September 2019, China, Afghanistan and Pakistan decided to officially extend the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), China’s flagship project under the BRI, into Afghanistan. In China’s calculation, the planned extension of the$61 billion CPEC into Afghanistan could be an essential solution to create a stable and terrorist-free Afghanistan. However, until now Chinese investments in Afghanistan have remained significantly low if compared with other nations such as Pakistan.

Huge investments by China under the BRI in Pakistan and the Central Asian nations neighbouring Afghanistan will in time create a diplomatic pressure from all the stakeholders on the new Taliban government in Afghanistan to ensure the stability of the country and to not allow it to be a safe haven for terrorism.

Conclusion

The Chinese have three complementary national interests and concerns in Afghanistan- first, they cannot see the country turn into a safe haven for terrorism (particularly in the form of ETIM); second, Afghanistan is geostrategically located within the vortex of the BRI; and third, China would like to benefit from the rich mineral deposits in Afghanistan. Moreover since distance matters a great deal in trade and transit, China would be willing to invest in projects to make condensed access a reality, provided the Taliban can guarantee safety of Chinese personnel and assets.

It is vital to note that Afghanistan has required external assistance in meeting not only its developmental programmes but even its basic national budgetary funding requirements. As aid payments from the West have been severely curtailed, the Taliban is looking towards China. Recently, China has announced a $31 million aid package for Afghanistan, in what appears to be one of the first new foreign aid pledges for the Taliban-ruled country. However, as Afghanistan is on the cusp of a humanitarian catastrophe and will need billions in aid to avert the possibility of universal poverty, it will be interesting to see if China is willing to enmesh itself in the murky development aid politics of the country.

China has made two vital gains by recognizing the legitimacy of the Taliban: first, China can hold the Taliban accountable for any attack on its citizens or assets emanating from Afghanistan and since the Taliban will be dependent on Chinese investments to a considerable extent, they will have to mend their ways; and second, China’s BRI will inevitably profit from stability in Afghanistan. Thus, China has done a good job of walking the tightrope in Afghanistan. A lot now depends on the Taliban’s policies which will decide China’s future engagement in the war-torn nation. For the present, it would seem like the Chinese strategy of courting the Taliban is paying off; but, whether it actually does, only the future will tell.

The author is thankful to her mentor, Ambassador Vijay K. Nambiar, former Ambassador of India to China and UN Secretary General’s Special Advisor on Myanmar, for his invaluable guidance and support in writing this article. The views expressed here are those of the author(s), and not necessarily of the mentor or the Institute of Chinese Studies.