Bhavana Giri, Research Intern, Institute of Chinese Studies

Automobile sector in China is the largest in the world when measured by the number of units produced. Apart from domestic production, people’s demands for all kinds of vehicles in China are met by Joint Ventures (JV). For a foreign company to establish a JV, it is required to enter into a 50-50 partnership with a Chinese company in order to start production in China; a similar arrangement is required for foreign companies to export automobiles to China.

Automobiles from the US are one of the most significant exports to China, ranking just behind aircraft and agricultural output. With a trade value of more than $10 billion, this sector is of great significance to the ongoing trade war. Currently, the automobile sector in China is witnessing a downfall in output growth when taken as whole which is driven by a drop in the production of gasoline based automobiles. However, in the long run, China’s drive to lead in global production of new energy vehicles (NEVs) is slated to offset this downturn, even if the trade war continues. Additionally, the upper hand China has in the automobile joint ventures will also help to recover from the downfall. In contrast, the resilience of China’s NEV sector will adversely impact the competitiveness of its American counterpart.

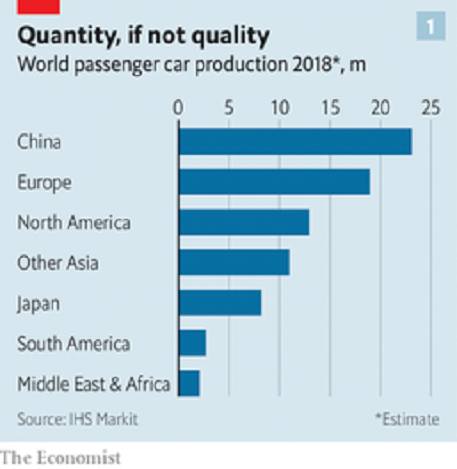

Demand side conditions are highly favourable and will continue to be so. Three decades ago bicycles were the most popular mode of transport in China and most cars needed to be imported. Today, however, Chinese car makers are producing more cars than any other country in absolute terms. As can be seen from the data, the production of automobile in China increased from 9 million units in 2007 to 23 million in 2018. To be sure, economic conditions are currently turbulent in China.

Observers predict that China’s GDP will decelerate in the near future and its leaders have urged precaution in this regard. The automobile sector, however is poised to remain buoyant, despite macroeconomic woes. The Chinese government intends to prioritise the preservation of automobile demand and supply by providing subsidies and exempting consumers from purchase tax on electric vehicles. These subsidies will ensure that there will be no significant shock to the automobile sector.

China has become the biggest giant in the production of electric cars and bikes. With Domestic Value Addition (DVA) of more than 80 per cent, and a strong grip over the production of essential inputs such as batteries, the sector enjoys a substantially strong footing. Recent falls in automobile stock prices should not obscure this fact.

To the rest of the world, it may appear that China has struggled to make progress in automobile manufacturing. However, the situation has changed drastically with recent developments. China now possesses massive potential for substituting imported automobiles with electric vehicles. With trade talks in a state of disarray and the heightened possibility that China will reapply auto tariffs, it is also likely that automakers will be incentivised further to produce in China. With the exception of the luxury segment, which is less easily substituted, China’s automobile sector is likely to withstand the headwinds it currently faces. Moreover, with the Chinese government establishing stricter norms for controlling carbon emissions and attempting to reduce pollution in cities, the scope for domestic companies to defeat automobile giants such as Toyota, BMW, etc has escalated. The Chinese government is also granting special manufacturing permits to companies which are working to develop NEVs.

The electric vehicle world sales database shows that in 2018, 2.1 million units of electric vehicles were sold which is almost 64 per cent higher than that of 2017. China has advanced its position in this particular segment and has a share of almost 56 per cent of the total sales. Although companies like Tesla, Toyota, etc. are also developing electric vehicles they lack the cost advantage China has, and are, thus unable to capture the market. Several subsidies and tax cuts provided on purchases of electric vehicles further boost demand in the highly populated cities of China. This is illustrated by the fact that profits for BYD jumped 632 per cent jump in 2019. On the other hand Tesla, which is exporting to China in an increasingly hostile trade environment, lost nearly $700 million in the first quarter in 2019, despite robust demand.

Another factor that will support China’s automobile sector is technology transfer. Most automobile production in China happens by way of Joint Ventures (JV) between Chinese and foreign companies, which allows local companies to acquire know-how. The Chinese have also acquired automobile technology by heavily investing in foreign-based automobile companies. Therefore, China’s automobile sector is unlikely to reel in the long-run. Moreover, China is less dependent on foreign value addition than it used to be – its contribution to processing and non-processing value addition process in the production of automobiles is uninterruptedly increasing.

The optimism expressed above does not apply to the American automobile industry, however. To a large extent, US-based automobile companies are dependent on revenues from the Chinese market that their JVs enjoy and are, thus, highly vulnerable to disruptions in bilateral relationship between two nations. For example, automobile giant BMW, is not introducing a new model because of the environment of uncertainty created by the trade war. US automobile companies are experiencing sluggish production while on the other hand Chinese NEV start-ups and companies are scaling up their production.

Unlike others, the automobile sector in China will likely remain profitable irrespective of ongoing trade contestations and tensions, due to the Chinese government’s encouragement to develop NEVs. China’s NEV companies are poised to emerge as leaders in markets all around the world, as they race ahead their counterparts from the US, Japan, and Germany.