Bihu Chamadia, Research Intern, ICS

China announced a nationwide lockdown on January 23 to combat the Coronavirus outbreak. As soon as there was a visible decline in the number of reported cases of COVID-19 in China, the rules of lockdown were eased and many government offices started to function normally. While China tries to pull itself out of the pandemic, there has been another outbreak in the country: the rising cases of divorces.

After the government started lifting the lockdown in late February, marriage registration offices of various districts started receiving high number of divorce cases. The offices of many districts in Xi’an city of Shaanxi province received a record number of divorce cases. According to local Chinese sources, the incoming divorce cases in the marriage registration office in Yanta district in the city of Xi’an had surged to the point where the marriage registration office did not have vacancy till 18 March this year. The situation was similar in other parts of China including Beijing, Shanghai, Yunnan and Sichuan.

Even though an increase in divorce cases is a common trend in China after the Spring Break, according to a report in Global Times, compared to the same period last year, there has been a surge in the number of divorce cases this year. In Tongzhou district in Sichuan Province, the Civil Affairs office received 232 cases from late February till end March, while the number of divorce cases registered last year during the same period was 180.

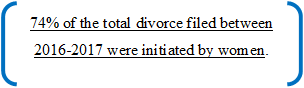

Marriage as a social institution in China has been facing serious challenges since many years. According to the Ministry of Civil Affairs, there has been a significant hike in the rate of divorce since the reform and opening up era. But this trend witnessed a steep rise after the liberalisation of Marriage Law in 2003. Once considered a taboo, even the number of divorce cases doubled in the past one decade. In 2010, the total number of divorces in China stood at 1.96 million which has more than doubled recently. Recent figures mentioned by Ministry of Civil Affairs, shows that it stood at more than 4 million in 2019.

The closing down of factories during the lockdown which had led to the laying off of workers and a dip in household income, was one of the primary factors that contributed to rising tensions between married couples during this period. Moreover, the gendered nature of household chores, where it was socially accepted that men who worked outside the household did not have time to lend a helping hand for household chores, was effectively busted during the lockdown when work happened from home; household work was still managed by the female partner during the lockdown. Women had to shoulder the entire burden of household duties including grocery-shopping and taking care of children with little to no help from her male counterpart. While these issues existed earlier, the lockdown period witnessed an overlapping of mental pressure along with problems such as inequality, gendering in roles and stereotyping of work which eventually accelerated divorce cases after the lockdown was lifted.

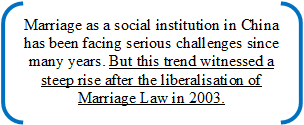

Infidelity was another major reason for divorce among married couples. The changes in the Marriage Law in 2003 allowed wives the right to divorce if the husband was abusive or had an extramarital affair. Many cases of infidelity were uncovered during the lockdown which otherwise would have remained under the veil during normal conditions. According to a 2016 report in Global Times, on an average 75% of the divorce cases filed are due to infidelity. In a speech made of 6 November 2019, Zhou Qiang, the Chief Justice of China’s Supreme People’s Court mentioned 74% of the total divorce filed between 2016-2017, were initiated by women.

While issues such as infidelity, financial issues and non-sharing of household burden have been the most common reasons for divorce in China, the lockdown aggravated these issues and exacerbated tensions between couples, and even led to a spike in cases of domestic violence. Divorce lawyers, in particular, have noted an increase in cases related to divorce and pointed that problems which would have earlier been a cause of little strife in the household were now leading to divorces due to an increase in interaction between couples during this period.

A combination of better socio-economic status leading to new aspirations, increasing tolerance among the masses towards divorce have influenced this trend. But most importantly, the liberalization of the marriage laws in 2003 played a significant role in the rise in divorce cases in China. Changes in the marriage laws in 1981 and 2001 led to a gradual increase in the number of divorce over the years but it was after the amendments in the Marriage Law in 2003 such as lower cost of filing divorce, faster pace of granting divorce and non-requirement of employer’s approval for filing a divorce which made it easier for women to seek divorce leading to the number of divorce in China rise exponentially after 2003 (see graph below).

Parallel to these developments was the rising average income of the female population in China since the reform and opening up. As average female income rose, the number of divorces also began rising. Earlier, job stability and owning a house were enough for a woman to ‘settle down’ but as women become increasingly educated and financially independent, their expectations also expanded. They no longer accepted to live in an abusive marriage or marriages where there was no compatibility. Moreover, while in the past, custody of the child was often given to the ex-husband after divorce and the wife was ostracized and faced difficulty finding a job – a major deterrence for women to seek divorce- this has changed today due to change in the level of income of women in China. Therefore, an already rising trend in the number of divorce cases witnessed an acceleration during the lockdown period when couples were forced to live together.

Although revoked, the demographic shifts caused by the One-Child policy is now causing a ripple effect both on China’s economy as well as the society. A rapidly ageing population and a fall in the average age of workforce have become a major concern for the central government as it grapples with lower birth rates and shortage in cheap labour. In 2019, China’s birth rate fell to its lowest in seven decades causing massive concern of the CCP. China’s population dwindles and the rate of marriage also goes down, the Chinese government fears that the number of workforce, taxpayers and consumers will also witness a steep fall.

The growing concern of the government towards rising divorce cases is reflected in the measures taken to address to issue such as free counselling for couples and the introduction of a “cooling off” period to slow down the divorce rate. While earlier it was adopted only by a few local courts, recently, the 13th National People’s Congress that took place in May 2020, voted in favour of adopting ‘cooling off’ as a part of China’s first ever Civil Code. This has caused a massive outrage among the Chinese population where the Party has been accused of abandoning progressive ideas of promoting gender equality. On the other hand, family planning policy which, in 2016, was amended to allow married couples to bear two children has been absent from the 2018 Civil Code draft. This has led to speculations of government further easing the restrictions on family planning or scrapping the bar altogether on the number of children a married couple could bear.

Despite government efforts to prevent any fissures in the institution, and its push to preserve “traditional values” for a stable and “harmonious society”, divorce cases in China continue to rise. The Covid pandemic has only acted as a catalyst that has unravelled the pre-existing fractures in the society and economy. Rising costs of social pension and shortage in supply of cheap labour have created a huge burden on the falling GDP of the country. As demographers warn that China’s population will begin to shrink in the next decade derailing China’s economy with far-reaching global impact, the need to preserve the institution of marriage has become even more important. The recent adoption of the Civil Code where marriage takes up considerable space in the text of the Code exhibit the gravity the case of rising divorces pose for Beijing.