Sanjana Krishnan, Research Intern, ICS

The death of Mao Zedong in 1976 gave rise to a series of dramatic political changes that led the emergence of Deng Xiaoping as the next leader of the country. Deng led China through a path that has now made the country the industrial giant it is now. This was made possible through Deng’s policy of ‘Reform and Opening Up’ and the “Four Modernisations”. What fuelled this industrial expansion was a heavy dependence on energy giving birth to a new vulnerability to China, namely energy security. While China is still heavily dependent on mostly its own coal reserves and imports of coal for its energy requirements, the reliance on imported crude oil is also increasing.

In 2017, China became the largest importer of crude oil in the world, surpassing the United States and 70% of this was met through oil imports mainly from the West Asian region. In the coming twenty years, these oil imports of China are expected to grow by 10%. Therefore, energy security and oil supply in particular have profound importance for China considering that the huge and powerful economy of China might derail and dwindle if that oil supply diminishes leading to not just an industrial break down but also impact on the China’s overall credibility as a great power in the world which rests, to a great extent, on its economic prowess. The dependence of the Chinese economy on its oil imports is thus an established and critical fact.

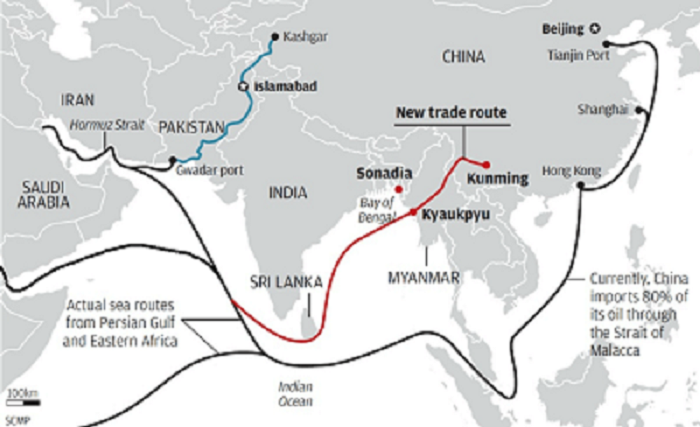

The transport of oil through the maritime route from West Asia to China passes through many strategic choke points. One of the most important among these is the Malacca Strait through which 80% of the energy import to China takes place. More than 50,000 merchant ships ply this narrow strait which amounts to 40% of the world trade. China’s economic security is closely tied to maritime trade security as 60% of its trade value travels by sea. Much of the trade between Europe and China enters the South China Sea through the Strait of Malacca. Similar is the case with the trade between China and Africa. Therefore, even for trade, the Malacca Strait holds significance for China.

Lying between the island of Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula, this narrow stretch of water known as the Malacca Strait is the main shipping channel between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean and is one of the most important shipping channels in the world. However, this strait is not depended upon only by China but other major powers too which has been a concern for the Chinese leadership in the past, fearing that these powers might be trying to control the Strait. A control of the Strait of Malacca by anyone will also mean that they control the oil routes to China and thus the economy too indirectly. This created what is known as ‘The Malacca Dilemma’, a term coined in 2003 by Hu Jintao, the then president of China. When it comes to the Strait of Malacca the fear of other states controlling this strategic transit is greater than the ambition to control the Strait itself.

In 2003-04, here was a threat of piracy in the region which the littoral states, namely Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore were able to curb to a large extent. This however gave an opportunity to states like US and Japan to try to get more involved in the region in the name of security, which China heavily criticised. The littoral states invited capacity building and rejected permanent stationing of any outside power. Singapore, which is in the southernmost tip of the Malacca Strait has excellent relations with the U.S. The relations between U.S. and Indonesia are cordial.

ASEAN being the collective voice of the region has a strong say in the functioning of the Strait. Following the threats by piracy and great power involvement, today the countries of the ASEAN have sought to create a Peace and Security Community (APSC) based on three key characteristics: a “rule based community of shared values and norms”; cohesive, peaceful, stable and resilient region with “shared responsibility for comprehensive security”; and a dynamic and outward looking region in an integrated and interdependent world. But the relations between China and many of the ASEAN states have been soured due to differences in territorial claims in the South China Sea. This has added urgency to China’s need to find an alternative to the Malacca Strait. Moreover, in the recent past, India has increased her naval presence in the Andaman Sea from its base in the Great Nicobar Islands largely due to its own perceived threat perceptions emerging from China’s ‘String of Pearls’ that have emerged as a result of the Chinese activities of the past. Given its projection capabilities in the Indian Ocean, the Indian Navy is able to keep a close watch on the PLA Navy in the region.

However, China has a few options in hand which are costly but worth trying. The Kra Isthmus Canal seen to the Asian Panama Canal as well as the Strategic Energy and Land Bridge have both seen a lack of much enthusiasm due the massive cost as well as the lack of trust between China and Thailand. Thailand is considerably powerful and will be hard to press. The Lombok and Makassar Strait are longer routes and would have additional shipping costs which can reach more than $200 billion per year making it a less viable option.

While nothing currently has the capacity to completely replace the Malacca Strait, two options available for China that can completely avoid passing through the Malacca Strait and many of the other strategic choke points is the Gwadar-Xinjiang pipeline and the Myanmar-Yunnan pipeline, although the latter can be affected by Indian presence. These options serve the additional purpose of opening up lesser developed regions of China like Xinjiang and Yunnan. The Gwadar-Xinjiang line will allow the Chinese energy imports to completely circumvent the Malacca Strait. However, the pipeline in Pakistan is faced with major logistic difficulties due to some of the harshest and the most rugged terrains in the world being present there, which can prove technically difficult as well as very expensive to navigate. The region is also ridden with terrorist activities which can potentially disrupt the supply or if the worst materialises, control these and be at an advantageous bargaining point. All these factors stand as difficulties that require investment in the form of infrastructure and security.

The Kyaukpyu Port which is being developed by the Chinese government in Myanmar is another alternative for China. The oil from the west can be docked here and transported to China via the Myanmar-Yunnan pipeline. However, now the pipeline only transports 420,000 barrels per day compared to the 6.5 million barrels per day that pass through the Strait, bound to China. The speeding up of the China sponsored infrastructural development, as a result of the increasing ties between the two countries, which was cemented during the January 2020 visit of Xi Jinping to Myanmar, has the potential to solve this problem to some extent. However, it cannot increase the capacity of this alternative as much as the Malacca Strait. Therefore, comparing the capacities of the various alternatives available to the Malacca Strait, it is evident that there is no single replacement for the latter. China can rather rely on multiple routes for the transfer of energy sources and trade to sustain the humungous economic machine. It is to be noted that the multiple alternatives, with efficiencies which cannot rank up to the Malacca Strait pose a dilemma in solving the Malacca Dilemma. Thus, the best option that China has in hand is to lower the contestation in the Malacca Strait and to find a peaceful way to work with.