-Sunidhi Khabya, BA, LLB (Hons), Second Year, National Law University, Jodhpur

Introduction

A maritime lien can be generally defined as “a charge upon maritime property, arising by operation of law and binding the property even in the hands of a bonafide purchaser for value”. Maritime liens are legal claims against a ship or its cargo for unpaid debts or damages, essential for securing services provided to the ship or addressing damages caused by it. Given maritime trade’s integral role in global commerce, understanding and enforcing maritime liens is crucial for financial security and smooth operations in this sector. “In the contemporary world, where more than 80% of the goods are transported by sea” it is an imperative to regulate this mode of transport by extensive and well-established laws to adjudicate conflicts.

The People’s Republic of China (PRC), a significant player in global maritime trade, has witnessed an increased reliance on exports. As most trade occurs via sea, the provisions governing ships and cargoes are vital in resolving disputes. Clarity on China’s maritime lien laws, in comparison to other major maritime nations, is crucial for protecting economic interests and ensuring smooth international trade operations.

Since the establishment of the PRC in 1949, there has been a huge shift in the domestic maritime laws of the country. At the time of its formation, the PRC did not have a well-established law for governing the seas. The evolution of maritime law in China can thus be divided into three phases for ease of understanding.

The first phase can be deemed as the Period before Reforms (1949-1978). This was a stage of slow development in the laws of the sea in China. In this phase, there was no established legislation for maritime law and marine disputes were instead governed by ordinances, regulations and statements issued by the government of China, further there was no issuance of regulations on specific subjects like ‘maritime lien’, and the orders for the laws of the sea were limited in number and were vague in nature. In essence, maritime lien laws were governed by internal regulations and policies. Thus, the development of maritime laws was slow and scarce during this phase.

The second phase was the Reform Phase (1980-1999). China opened up its economy in 1978 after years of state control. As international trade began to flourish for China, a more uniform and sturdy legal system was required to regulate maritime trade and transit in order to secure and support trade through the seas. The need for a formal legislation was felt as a majority of trade occurred through maritime routes. In the early 1980s, China began drafting its domestic legislations on maritime law relying upon international conventions such as UNCLOS, which “was promulgated in 1982, and China ratified its accession to UNCLOS in 1996, using its relevant provisions as a template for its marine legislation, with some of the provisions of its domestic legislation drawing entirely on the content of the relevant provisions of UNCLOS”. Further in 1984, the PRC conducted an “International workshop at Dalian under ESCAP” in order to assist the government in preparing the maritime laws of China, where “the subjects chosen by the Chinese Authorities for the first seminar were Maritime Liens and Mortgages and Arrest of Ships”.

Further, in 1992, the most important legislation for governing maritime liens in China titled, “The Chinese Maritime Code”,was enacted. This legislation provides an extensive legal framework for maritime liens in the PRC. Chapter I, Section 3 of this code deals with all the aspects of maritime lien. ‘Article 22’ of the code, which clarifies who is entitled to the right of a maritime lien, extends the scope by giving priority orders for wages and other remunerations, claims for loss of life due to operation of the ship, salvage, compensation for ship collisions and claims for pilotage fees; and ‘Article 25’ provides a priority order for allowing a claim of maritime lien, wherein it has priority over possessory lien and ship mortgage.

Another important legislation is the “Special Maritime Procedure Law of The People’s Republic of China, 1999”. This law refined the procedural aspects of the law of maritime lien and provided further clarity over its enforcement in China. Chapter XI of the statute deals with the “Procedures for Publicizing Notice for Assertion of Maritime Liens”. The law introduced mechanisms for the arrest of ships and other means so that the claimant could secure his claim before the final resolution of the dispute; this increased the people’s confidence in the Chinese legal system. This law significantly modernised the maritime lien laws of China, making them more efficient and conducive specifically in cross-border marine disputes.

The third phase is the Post-Reform Phase (2000-Present). Since the development of the basic legal framework for Chinese marine laws, the Chinese government has ensured that the laws are in congruence with the needs of the parties. With the advent of the new century, China’s maritime industry has grown and developed, which has also led to a greater number of cross-border disputes due to burgeoning international trade. The Supreme People’s Court, which is the apex court of the PRC, has played a major role by issuing its interpretations on the legislations, which have further clarified the scope and application of maritime lien provisions, especially in cases involving foreign parties. A liberal interpretation, by including prevalent international practices when dealing with maritime lien disputes is adopted by the court when the parties involved are from foreign jurisdictions.

Thus, it can be said that maritime lien laws in contemporary China have come a long way from the laws that were in force at the time of the formation of the nation. Although China may not have implemented several key international conventions on maritime lien laws, but internationally accepted principles still find a place in the interpretations of Chinese laws while at the same time retaining their unique features. This makes China an attractive nation for maritime trade. The legal framework is still evolving with the dynamic needs of the world in order to meet global standards. It is, therefore, vital to understand the differences in laws of the PRC and other important maritime jurisdictions.

In China, the maritime lien laws have developed gradually and assimilated internationally accepted principles within them through the interpretations of the judiciary. A unique aspect of the Chinese laws is that they are drafted in a way to provide top priority and protection to claims for personal injury and salvage. There is no general action in rem for maritime lien in the PRC.

“According to Article 22 of CMC, the following five categories of claims give rise to maritime liens: (a) claims for wages, other remuneration, crew repatriation and social insurance costs made by the Master, crew members and other members of the complement;(b) claims in respect of loss of life or personal injury occurred in the operation of the ship; (c) claims for ship’s tonnage dues, pilotage dues, harbour dues and other port charges; (d) claims for salvage payment; (e) claims for loss of or damage to property resulting from tortious acts in the course of the operation of the ship.”

The claims as listed above are paid in this order, so the claim for crew wages takes precedence over any claim for damage to property. However, the salvage claim is given priority if the ship was salvaged after the other claims arose. This is because without salvage the ship would not be able to settle other claims. The claim that arose at a later date is paid first in case of multiple salvage claims. Giving priority to crew wages shows China’s values of protecting worker’s rights and social welfare.

In India maritime lien is governed by “The Admiralty (Jurisdiction and Settlement of Maritime Claims) Act, 2017”, and as per Indian law, maritime lien confers both jus in re and jus in rem rights to the claimant against the vessel.

“Indian courts have consistently reinforced the principles governing maritime liens through various rulings. In M.V. Elisabeth v. Harwan Investment & Trading Pvt. Ltd., the Supreme Court of India established the broad admiralty jurisdiction of Indian courts to arrest foreign ships, extending the application of maritime liens to international shipping disputes. In M.V. Sea Success I v. Liverpool and London S.P. & I Assn. Ltd., the court delved into the priority of maritime liens, reaffirming the doctrine that the most recent lien holder’s rights are superior. The court also emphasised that maritime liens attach to the vessel independently of the owner’s actions. Further, in Sethusankar Shipping Corporation v. Indo Marine Agencies, the court addressed claims related to crew wages, clarifying the extended period for such claims under the Admiralty Act. The court’s ruling reinforced the two-year period for enforcing maritime liens related to crew wages and repatriation costs.”

Indian maritime law has developed significantly due to the liberal and flexible interpretations by the judiciary.

The United States has one of the world’s most extensive maritime lien law frameworks. The “Commercial Instruments and Maritime Liens Act” is the governing source for maritime liens in the US. A unique aspect of American law is maritime liens for necessaries, in that “a maritime lien also comes into effect the moment the ship loads or purchases “necessaries”. Necessaries are items and services that are essential to the correct operation of the ship, or to keep it out of danger”.These necessaries include fuel, towage, repairs, pilotage, and ship equipment among others, which are required and without which the ship will not be able to perform its function. The claim for the lien has to be settled through the property or the vessel itself, which means that the ship owner’s other property cannot be claimed instead and if the vessel is destroyed, then the lien is lost. The priority order is different than China’s; herein, highest priority is given to Seamen’s wages, followed by salvage, collision, ship mortgages and necessaries. The US also allows the ‘in rem’ proceedings that are directly against the vessel which allows the ship to be arrested and sold in order to meet the claim.

In the United Kingdom, maritime lien law is regulated by the “Merchant Shipping Act, 1995”, and it has been codified under “Section 21(3) of the Senior Courts Act, 1981”. “In England and Wales the term ‘maritime lien’ applies only to a select group of maritime claims, being seafarers’ wages, masters’ wages, masters’ disbursements, salvage, damage (caused by the ship), bottomry and respondentia. Other maritime claims exist, such as services supplied to the ship (for example, bunkers, supplies, repairs, and towage), as well as claims for cargo damage, for breaches of charter party and for contributions of the ship in general. However these maritime claims do not give rise to maritime liens but only to ‘statutory rights in rem’, which are rights granted by statute to arrest a ship in an action in rem for a maritime claim.” English law does not recognise the lien for necessaries; a claim for necessaries can be pursued as a statutory right but it will not be considered as a lien. English law also recognises the principles of equity and thus the courts have discretion while determining priority order for maritime lien.

Due to the ever-growing importance of maritime trade and its international nature, it has become imperative to establish some uniform and consistent maritime laws which would be accepted by these major marine nations around the world unanimously. The first step in this direction were the international conventions on maritime liens of 1926 and 1993 which have significantly influenced the laws of these nations, although their interpretations have varied across them. The trends suggest that with the increasing importance and relevance of maritime trade, and the increased influence of globally recognised principles, maritime lien laws might gradually become uniform through amendments in the domestic laws of countries. However balancing international conventions with domestic laws is important and this is recognised by major nations.

However the problem of consensus is a major hindrance in the way of a globally accepted maritime law. The lack of uniformity and uncertainty for various shareholders led to the failure of the conventions of 1926. The failure of the International Convention on Maritime Liens and Mortgages, 1993 — which sought to modernise and expand upon the 1926 convention — can largely be attributed to its inconsistent interpretation across countries, and its conflict with domestic laws. Even signatory states delayed ratifying it due to these issues.

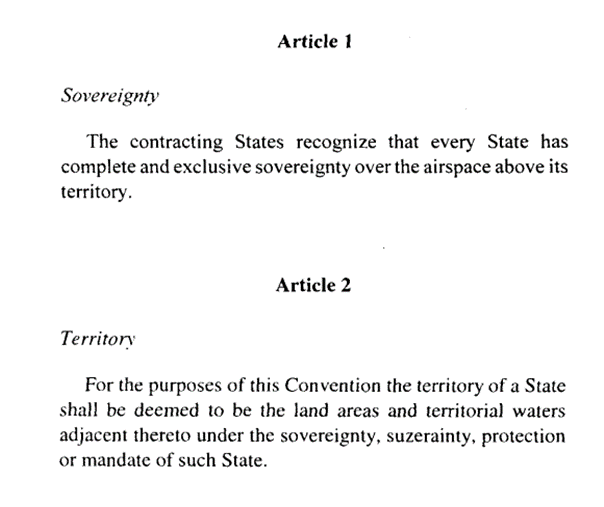

While these conventions have made a noticeable attempt to streamline maritime lien laws globally, they have been relatively ineffectual in doing so. The major cause for this is the reluctance of important maritime nations toward ratifying and implementing the international conventions signed for maritime lien laws. Another important point of concern is the hesitation of the signatory nations of the treaties to form laws conforming to the conventions signed. The nations that have adopted laws based on these conventions have given them their own interpretations and thus the local laws remain largely varied in the major as well as minor maritime nations. This is troublesome, as in the cases of international maritime disputes (which are frequent due to the ever-growing importance of maritime trade and transit) the involved parties often have jurisdictional disputes. There is, in practical effect, no clarity as to what law will be applicable in a particular situation and the case can drag on for years without the serving of proper justice to the lien holder. This raises the question: why not make such laws binding? The issue with this is that many nations already have well-established admiralty and maritime law systems. Binding agreements would mean disrupting these entrenched legal systems and could be seen as a potential threat to the sovereignty of the countries, which would mean that such a proposition would be met with protests and trepidation from most of the nations.

In a nutshell, although the conventions have considerably improved and clarified maritime lien laws, there is a long way to go in terms of establishing uniform and consistent maritime lien laws accepted by all major maritime nations of the globe. The problems arise firstly in adoption, ratification and then in the practical implementation of these laws in real life cross-border disputes. International institutions like the International Maritime Organisation can play an important role in convincing nation-states for adopting an improvised version of the international conventions on maritime liens. The amendment of rules under UNCLOS to include maritime lien laws and priority order rules for them could lead to substantial progress. It must be accepted that in order to streamline the laws, a compromise will have to be made by the signatories for better governance. The question arises as to whether a binding international admiralty law can be implemented globally, and to what extent such a framework would affect domestic legal systems.

Thus it can be stated that maritime lien although finds its place in the laws of all important nations, there is a need for bringing uniformity and consistency in these laws. In the context of the PRC specifically, the laws regarding maritime lien have been standardised through gradual evolution with time, but an international law — which is accepted by most maritime jurisdictions is imperative to keep up with the needs of the world, and in order to facilitate trade and adjudication of conflicts in cross-border as well as domestic disputes.