Siddhant Hira, China-analyst and incoming MA National Security Studies student at King’s College London

Introduction

Just like Beijing’s 2008 Summer Olympics, the run-up to the 2022 Winter Olympics also has “angry pro-Tibet protests along much of the Olympic Torch relay.” 2008 was a watershed moment in Chinese foreign policy: the Games was a major soft power victory. China proved to the world that it was capable of hosting a green and high-tech event by investing $40 billion in four years.

Chang Ping puts it aptly: pre-2008, ‘connecting the world’ was popular but post the games, China’s new message was “now the world should follow us”. At that time, the Olympics was a sports diplomacy tool for it to consolidate its status as an emerging superpower. A 2009 Congressional Research Service Report stated that after the Beijing Olympics, China’s economy enjoyed a domestic boom while its international trade and investment declined sharply. By implementing economic measures for short-term benefits, Beijing projected the image that its economy was surging despite the rest of the world combating global recession.

Beijing’s 2022 Winter Olympics will be the first to allow foreign visitors in the post-Covid world. It will certainly be a welcome distraction, both domestically and globally. Domestically, it is perceived as a potential major success: China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) outlines the country becoming a sports power by 2025 as one of its long-term goals. China wishes to use the Games to fabricate a diplomatic victory after Covid-19 by inviting the world to witness first-hand, on-the-ground Chinese economic and soft power.

Today, China faces a credibility crisis ahead of the Olympics that is not just economic but an amalgamation of military, political, human rights and democratic challenges. China is not yet a global superpower but is much stronger than in 2008; however, now it has a different agenda for the 2022 Winter Olympics: a reset in its global perception and a restoration of credibility against the backdrop of Covid-19.

Loss of Face?

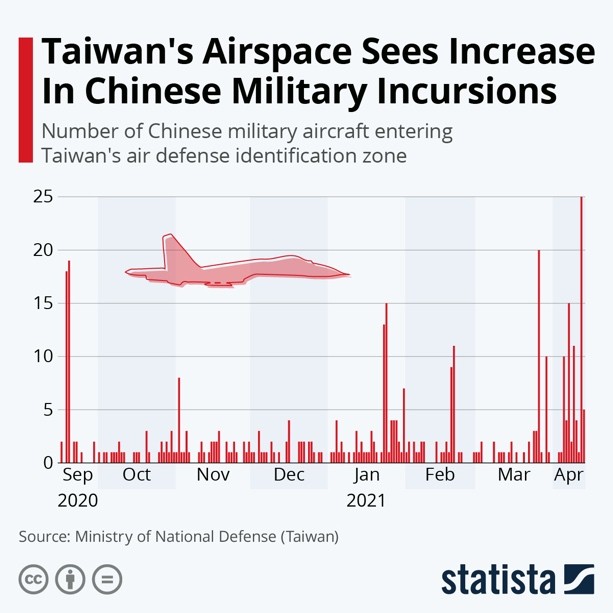

For decades, China has maintained an aggressive posture in the South China Sea, with numerous ongoing territorial and/or maritime disputes with nations in the region. Threats to and flight incursions over Taiwan continues to be a major issue. According to Taiwan’s Ministry of National Defense, the PRC has violated Taiwan’s air defence identification zone (ADIZ) 380 times in 2020, a record figure. It does so in three ways, from most to least common: “circumnavigational flights of Taiwan, ADIZ intrusions, and violations of the cross-strait median line.”

Source: Statista

In recent times, there have been two heavyweights in Tibet’s corner: the United States (US) and Great Britain (GBR). The former passed the Tibetan Policy and Support Act in January 2020 in Congress: Tibetans choose a new China-independent Dalai Lama, strict measures against Chinese officials who interfere in his succession, environmental protection of the Tibetan plateau, potentially no new Chinese consulates in the US until a consulate in Lhasa and recognition of the Central Tibet Administration. Just two months later, GBR’s Foreign Secretary, Domininc Raab, spoke at the United Nations Human Rights Council, stating that human rights abuses against Uighur Muslims were “… taking place on an industrial scale.”

On 30th June 2020, China circumvented Hong Kong’s legislature by passing a draconian national security law. This Law grants vast and extremely vague powers to the Chinese Government to curb dissent and protest; criminalises secession, subversion, terrorism and collusion with foreign/external forces. Even though China has faced heavy backlash from the free world, the law is still in effect and the democratic and humanitarian freedoms enjoyed by Hong Kong remain curtailed.

Source: Freetibet.org

2020 began with the grim news of Covid-19, with most of the world holding China responsible for its origins and development. One theory propounded is that it was intentionally developed in a Wuhan laboratory with links to China’s army – the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). The other theory considers it an accidental leak by human negligence.

Cases first emerged early November 2019, but the world only came to know in late December. Before the virus emerged, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) had conducted an exercise in August 2019 – Crimson Contagion – to simulate a pandemic originating in China. David Sanger of The New York Times said that the result of the exercise may have been alarming enough to be “marked draft, sensitive, not for distribution”. The numbers projected were extremely sobering: “90% chance that the pandemic will be of very high severity, with 110 million forecasted illnesses, 7.7 million forecasted hospitalizations, and 586,000 deaths in the U.S. alone.” There is no evidence of a published exercise report, nor of any follow-up action. Had necessary steps been taken, Covid-19’s initial impact on the American public health system would have been minimised. The US Government’s apprehension of this becoming public knowledge potentially allowed China to control the narrative by obstructing impartial and independent studies on the origins and development of the virus. But now, the US Intelligence Community is conducting a thorough fact-finding investigation on the direct command of President Biden.

For India from an international relations perspective in 2020, its two greatest challenges which continue to shape its policy are Covid-19 and the clash with Chinese troops in Galwan Valley on 15th June 2020. Soldiers from both sides came to blows in Eastern Ladakh, using clubs, stones, fists and the like – with India losing 20 men – and the Chinese – four, and possibly more. Typically, China takes decades to admit if and when it has lost soldiers in battle but this time, it took eight months. Forced by its own citizens sharing information publicly and with international sources quoting higher casualties, China had to admit its losses.

Source: South China Morning Post

Conclusion

China also lost, and continues to lose, face because of the Belt and Road Initiative, its alleged involvement in the Myanmar coup and the Uighur-related controversy surrounding the Disney film Mulan. Its medium of aggression is primarily wolf-warrior diplomacy, a term that has become synonymous with China’s foreign policy.

For any state, hosting the Olympic Games is an opportunity to display the strength of its public diplomacy, status and soft power. There have even been some comparisons between the 1936 Munich Summer Olympics and the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, and the significance for both nations. The Biden administration is yet to take a stand regarding any boycott – with various stakeholders expressing a range of reactions including outright boycott, hosting elsewhere and legally punishing sponsors. Political leaders across North America and Europe have also coordinated legislative action against China hosting the Games.

The greatest challenge for the democratic world order is to ensure that the spirit of the Olympics is upheld, and yet strong action is taken against China’s humanitarian track record. The question facing China is whether it will be able to reset its image to the pre-Covid era, or has it already done irreversible damage in the eyes of the free world.