My visit to Santiniketan, India, in January 2019 was to continue the journey my father artist Xu Beihong had started there between 1939 and 1940. At the invitation of the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore, Xu Beihong went to India at the end of 1939, holding an exhibition at Visva-Bharati and another in Calcutta in the following year. Rabindranath Tagore had established Visva-Bharati to offer the studies of all the components of Eastern civilization in one place and Chinese civilization was one of Tagore’s major focuses. A most influential Chinese painter and teacher, Xu Beihong came to Santiniketan as the first Chinese visiting professor of Kala Bhavana, the art school at Visva-Bharati, which had been eager to get a broad view of Chinese art. He lectured and demonstrated Chinese ink brush painting and calligraphy to Kala Bhavana students.

Xu Beihong (1895-1953) is widely known as the father of modern Chinese painting. Born into a poor family in Yixing, Jiangsu Province, he learned Chinese classics and traditional Chinese painting from his father, a self-taught artist.

One of the first Chinese art students to study in Europe, Xu Beihong in the 1920s graduated from the Ecole des Beaux Arts. Returning to China in 1927, he successfully integrated Western painting methods and techniques with traditional Chinese painting in order to develop Chinese painting. Xu Beihong pioneered China’s art education. From 1927 until his death in 1953, he trained several generations of Chinese artists.

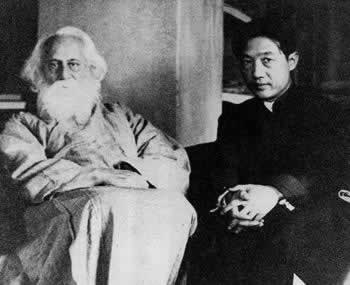

Admiring Xu Beihong’s art, Rabindranath Tagore wrote an introduction to Xu’s exhibition. In response to Tagore’s welcome address, Xu Beihong said: “Santiniketan is a place which corresponds to my ideal of a center of art and culture. The whole world should make a pilgrimage here in order to breathe the joyful atmosphere of creative endeavour undertaken here under the direct inspiration of India’s great poet. My visit here is that of a pilgrim. I have come not to give but to receive the great gifts that India may have to bestow upon my country and people as she did in the days gone by.”

Now I understand why my father made such a comment. Rabindranath Tagore’s poetic lines, his sensitivity to the beauty in nature and his ability to capture the soul of a human being really touched my heart. Tagore’s creativity made Visva-Bharati such a vibrant place. The short, yellow-colored buildings with light grey windows appeared lively. The dark-red leaf design patterns on the pillars and around windows suggest a sense of growth, symbolizing the intellectual growth of students. I hear these design motives have remained since 1940 or earlier.

Besides observing cultural activities and the magnificent landscape of the Himalayas and Darjeeling, which are reflected in his works, Xu Beihong interacted with outstanding cultural figures including the Nobel laureate Tagore and Mahatma Gandhi. Xu Beihong was moved by Tagore’s sympathy with China’s War of Resistance and his firm denunciation of the Japanese invasion of China. In his memorial speech for Tagore in 1941, he praised Tagore’s love of humanity that resonated in the whole universe. Describing his meeting with Gandhi on 17 February 1940, Xu Beihong wrote: ‘Today I felt truly honored to live with the soul of all India’.

This rich experience enabled Xu Beihong to create during his year of residence in India, a great number of masterpieces that exemplify the pinnacle of his artistic career. These include Portrait of Rabindranath Tagore, Portrait of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, The Foolish Old Man Who Removed the Mountains, depictions of the Himalayas and his famous ink brush paintings of horses. After his experiences with the horses in India, the horses he painted exhibit noticeably greater vigor.

There are nine original Chinese ink brush works by Xu Beihong at Visva-Bharati, including two in Rabindra Bhavana, the university museum, and seven in Kala Bhavana’s Nandan Museum. Among these works, Portrait of Rabindranath Tagore has the highest artistic merit. It is Xu Beihong’s representative Chinese ink brush portrait based on his many sketches of Tagore. A similar painting of Rabindranath Tagore is in the collection of the Xu Beihong Memorial Museum in Beijing. The accomplishment of this Chinese ink brush portrait is comparable to that of a Western oil portrait from life. Such a portrait from life revealing an individual’s facial expression and capturing his creative moment was unique in Chinese ink brush painting at the time it was done. I think that Xu Beihong must have given this portrait of Rabindranath Tagore to Visva-Bharati to honor his friendship with Tagore and also to serve as an example for the students to learn from.

To help research on Xu Beihong, I deciphered the inscriptions and seals on all the works by Xu Beihong in the twin museums’ collection and provided translation. The implications of these inscriptions and seals had not been known to scholars before. I also offered suggestions to both museums concerning preserving their fragile ink brush works by Xu Beihong so future generations in India and around the world will be able to understand and appreciate Xu Beihong’s art.

During my visit, Nandan Museum held an exhibition of paintings by Xu Beihong and other Chinese artists. Watching a Kala Bhavana professor and his students discussing the paintings at the exhibition, I was happy to share with them how Xu Beihong’s animal paintings express deeper meanings through the use of analogy implied in his inscriptions and seals. On his painting The Horse, he inscribed: “November 1940. Beihong painted this to congratulate Elder Tagore on his recovery from his illness. Gentle breeze and beautiful sun. The celestial and human worlds were celebrating.” Xu Beihong conveyed his happiness for Tagore’s recovery through this spirited horse and the artist’s inscription. One of the seals says: “Brilliant and Fluid,” expressing the joy through fluid brushwork.

Xu Beihong had received strong support for his exhibition in Calcutta, initiated by Rabindranath Tagore and held under the joint auspices of the Indian Society of Oriental Art, Calcutta, and the Sino-Indian Cultural Society, Santiniketan. Nandalal Bose, principal of Kala Bhavana, wrote an appreciation for the exhibition catalogue while another famous Indian artist Abanindranath Tagore opened the exhibition, which included among the 206 artworks Xu Beihong’s representative Chinese ink brush painting Jiufang Gao, Horse Judge and his oil history painting Tian Heng and His Five Hundred Warriors. Xu Beihong’s comprehensive exhibition strongly influenced artists and art lovers in India. He donated the entire proceeds from the exhibition to help alleviate the suffering of refugees driven from their homes in Japanese-occupied areas of China.

To learn more about my father’s experience in Santiniketan, I visited Professor Tan Yunshan’s old house behind Cheena Bhavana where Father had stayed. Tan Yunshan was founder of Cheena Bhavana. The earth color of the house is consistent with the design of other buildings in Visva-Bharati. The simplicity and openness of the architectural design allow ample space both inside and outside the house, which has several entries. I imagined Father walking in the morning around the open space next to the house, observing the large trees and birds carefully for his creative work. He made many studies of the red flowers on the huge silk-cotton trees, one of which grew in front of the Chanda house. Anil Chanda, Tagore’s secretary, and his wife Rani Chanda became Xu Beihong’s close friends. I also imagined Father chatting with his host Professor Tan in the evening, sharing his personal stories and his concerns for his country suffering from the Japanese invasion. Now the people in that once bustling house are gone, leaving only the old trees and birds to reminisce about the people and events that had taken place there.

In my lectures at Visva-Bharati I shared my understanding of Xu Beihong’s art, his Indian connection and my memoir Galloping Horses: Artist Xu Beihong and His Family in Mao’s China. Faculty and students appreciated my insight into Xu Beihong’s art and how his family and legacy had survived the turbulence of Mao’s ever-changing policies, which dictated the direction of art and music from 1949 through the devastating ten-year Cultural Revolution as described in my memoir. Students told me that I had enriched their experience. At the same time, I received inspiration from the creative environment of Visva-Bharati as my father had received in 1940. Viewing Father’s works in Santiniketan was like seeing his life experience in front of me. I felt rewarded to have contributed to Tagore’s Visva-Bharati as my father had done three quarters of a century before.

I appreciate the help from Dr. Tan Chung, Chameli Ramachandra, Srila Chatterji, and other people in Santiniketan.