Hemant Adlakha, Vice Chairperson, ICS and Associate Professor, Jawaharlal Nehru University.

This article was published two months ago in Modern Diplomacy under the same title. However, following the revival and fast spreading of local variants of Covid-19, including Omicron, first in Xi’an and then in Yuzhou city in Henan province, and now in the northern port city of Tianjin near Beijing, questions have been raised in China on the rationality behind persisting with “zero tolerance” policy. I hope to come up with the second part of the article with focus on resurging Covid-19 cases in China and the Beijing Winter Olympics.

Source: scmp.com

The world is again at war with China. This time, the war is not about China’s aggressive “wolf warrior” diplomacy; nor is it about China threatening to use force to reunify with Taiwan. Instead, if one goes by what the global media says, this new round of “war” is an ego clash between what China calls Covid-19 “dynamic zeroing” and what the West is practicing – “living with virus strategy.”

Last year, Dr. Li Wenliang, who raised an alarm about the coronavirus in the early days of the outbreak, was forced by the police in Wuhan to write “self-confession” and was told to immediately stop spreading false rumours. Within a few days, Dr. Li caught the infection and was hospitalized, where he succumbed to the virus and died three weeks later. Of course, Li was not infectious disease expert, he was an ophthalmologist at the Wuhan Central Hospital. A little over a year later, when Zhang Wenhong, a doctor in Shanghai who has been compared with the top US health official Dr. Anthony Fauci, wrote on his Weibo blog indicating China might have to live with the Covid-19 pandemic, he had to face vicious attacks by the official media and the Chinese health authorities. For, Dr. Wenhong had come in the cross hairs with China’s official “dynamic zeroing” strategy aimed at eliminating the coronavirus.

It is important to recall, since early last year China has been strictly adhering to a “zero tolerance” (Qingling in Chinese) policy for Covid-19, under which authorities have imposed strict border controls, travel restrictions, lockdowns and at times carried out mass testing as and when new Covid-19 cases emerged. Furthermore, the success of “zero tolerance” policy which resulted in long stretches of zero new cases was drummed up by the communist leadership of the country as the secret for successful coronavirus pandemic containment strategy. “China’s government attributed the effective virus containment to the phenomenal leadership of the communist Party and its institutional superiority over Western liberal democratic systems,” commented The Diplomat two months ago. (Emphasis added).

Source: Bloomberg.com

Rise in regional flare-ups

However, more recently, China experienced regional flare-ups of the globally prevalent delta variant, including in cities such as Beijing and Shanghai. As a result, Beijing authorities were forced to postpone the capital city’s annual marathon scheduled to be held on 31 October. A week earlier, on 24 October, Beijing’s Universal Studios theme park also took preventive measures and started testing all its employees after it was found out that a suspected case had visited the Studios. At the same time, Shanghai Disneyland and Disney town were temporarily shut down as part of the pandemic prevention drive. According to China’s English language newspaper, Caixin Daily, the decision to suddenly close Disneyland followed the emergence of a new Covid-19 case in neighbouring Zhejiang province, it was someone who had visited the Shanghai attraction.

In fact, the recent flare-ups spread across over twenty provinces and areas in China have been attributed to a cluster of Covid-19 cases in Ejin Banner in the remote Inner Mongolia that is in the Gobi region. According to reports, nearly 9,000 tourists who were visiting the Gobi Desert during China’s National Day “golden week” holidays were trapped there, mostly in quarantine. The Chinese tourists had gone there to spend time in the famous poplar forests where trees turn golden yellow during this time of the year. An official Chinese media outlet reported “the recent local Covid-19 outbreaks that began in mid-October have spread to two-thirds of China’s 31 provincial-level regions, with more than 1,000 locally transmitted infections.” Attributing delta variants as the cause for the country’s second wave of the pandemic, one of China’s top epidemiologists, Dr. Zeng Guang, a former head of Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC), opined China must continue with emergency measures, including maintaining long quarantines and vigorous contact tracing, until a “barrier of immunity” has been established.

Living with the virus” is more costly

While acknowledging that the global challenges in containing the delta variant will mean that society must learn how to coexist with Covid-19, Zeng emphasized that “China will need to continue its ‘zero tolerance’ strategy against Covid-19 with nationwide emergency responses.” Reacting sharply to the last of few remaining countries which too have finally shifted from eliminating strategy to trying to live with the virus – for example, New Zealand, Singapore and Australia – China’s most celebrated infectious disease expert and “national hero” Dr. Zhong Nanshan has strongly defended “zero tolerance” strategy on the grounds that measures to deal with sporadic Covid-19 outbreaks are less costly than treating patients after they have been infected. “The cost is truly high, but compared with not managing it, relaxing (the zero tolerance policy), then that cost is even higher,” Dr. Zhong Nanshan said in a recent TV interview.

Source: japantimes.co.jp

Remember, China has reported about 4,600 deaths due to COVID pandemic. In comparison, the US with just a quarter of China’s population and a far more expensive and superior health care system has lost over 755,000 lives. No wonder China’s foreign ministry spokesperson has recently disdainfully dismissed the US as an “inferior system” and a “total failure.” Defending the Chinese government policy, Dr. Zhong Nanshan questioned all those countries (mostly the developed countries in the West) that had relaxed their policies amid a drop in Covid-19 cases only to go on to later suffer a large number of infections. “The global mortality rate for people infected with Covid-19, which spreads fast and continues to mutate, is currently around two per cent. We [China] cannot tolerate such a high mortality rate,” the top Chinese epidemiologist said.

The logic of China’s “zero tolerance” policy

Refuting the logic offered by Dr. Zhong Nanshan in defense of China’s “zero tolerance” policy, i.e. it is more effective and less costly to contain Covid-19 than treating patients after they have been infected, an overseas Chinese scholar Zhuoran Li attributed China’s so-called success in fighting the pandemic to the Maoist doctrine of mass line and the CPC’s Leninist identity, respectively. “The key to implementing this ‘zero tolerance’ is the CPC’s mass mobilization capability. The CPC has viewed mobilization as a ‘secret weapon’ throughout its history. After Mao’s Mass Line became a key to the CPC’s victory in 1949, the Party continued to rely heavily on mass mobilization to achieve its goal – social transformation between 1949 and 1956; steel and food production between 1958 and 1961; or combating natural disasters in 1998 and 2008,” Zhuoran Li argues.

At another level, adding a different dimension to Zhuoran Li’s argument, another overseas Chinese scholar, Yanzhong Huang, a senior research fellow with the Council for Foreign Relations (CFR) has observed: “It’s becoming part of the official narrative that promotes the approach and links to the superiority of the Chinese political system.” Maybe true, however, from China’s point of view, what is most disturbing is there is a lack of consensus within the official narrative. Take Ruili for example, a southwestern city surrounded by Myanmar on three sides and currently the center of the highest flare-up. According to Ruili residents, they have been the worst victims of China’s zero-transmission strategy as they have been subjected to multiple rounds of quarantine, lockdowns and excessive Covid19 testing. The local city authorities have put the blame for the plight of the 270,000 residents on the successive flare-ups on “traders and refugees who frequently cross the border into China.” On the other hand, the angry residents in the city have been complaining of the escalating financial as well as social costs for having been left alone to cope with the epidemic.

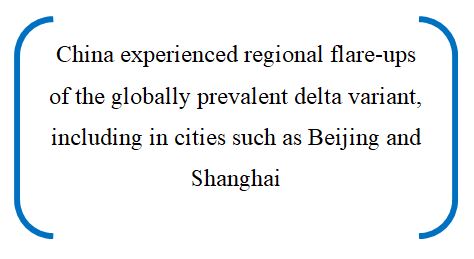

Source: economist.com

Furthermore, foreign experts and the global media have maintained that China either doesn’t want to admit or the authorities in Beijing are yet to realize – as most or nearly all countries have – that not only the virus is now permanent but also that there is no chance in the long run that a zero-Covid strategy could work in terms of achieving complete elimination. This confusion is the official narrative in China has been best manifested in a public spat between the mayor and the deputy mayor of Ruili. Last month, Dai Rongli, the deputy mayor posted an essay on his personal social media blog highlighting the difficulties city residents have been facing due to the pandemic prevention policies. “The pandemic has mercilessly robbed this city time and again, squeezing dry the city’s last sign of life,” the deputy mayor wrote. Within days, an infuriated city mayor Shang Labian criticized his deputy in an interview with a Chinese digital news platform saying: “Ruili does not need outside support and sympathy.”

To sum up, it is indeed true that most people in China support the country’s strict pandemic prevention policies. Yet undeterred by what most other countries are claiming, that is, “the illness will circulate in perpetuity and can only be encountered with high immunization rates,” the Chinese leadership is standing firm on its resolve that the zero-transmission strategy is less costly. Liang Wannian, the head of China’s “leading small group” under the Ministry of Health to combat Covid19, has refuted as baseless claims that China is persisting with its zero-transmission strategy for political reasons such as holding of the Beijing Winter Olympics in February 2022 and the 20th CPC National Congress in October next year.

Source: nytimes.com

“Dynamiczeroing is not zero transmission, nor is it China’s permanent strategy. Whether to change the current pandemic prevention strategy depends on the trend of the global epidemic, the mutation of the virus, the change in the severity of the disease and the level of vaccination coverage in China and other factors,” Liang said. In other words, Liang Wannian almost confirmed what experts outside China have been claiming: “They [China] are not confident about the effectiveness of [their own] vaccines – the ability to prevent infections.” Therefore, China has been caught in its own trap of “zero transmission” or “dynamic zeroing.”