P.K. Anand, Research Associate, ICS

Anticipation mixed caution prevails in the run up to the second informal summit between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the south Indian coastal town of Mamallapuram, in Tamil Nadu, this weekend. Given that the jury is still out on whether any substantive and tangible deliverables have been achieved from the first such exercise at Wuhan, in China, in May 2018, such an approach is understandable.

The optics of the meeting between the two leaders is expected to be political and strategic, even though economics looms as signifier for the relations of both countries in the background. Perhaps, it is a good time to analyse the economic capacity of China, especially the role of manufacturing sector, in powering the country and its positioning in the China-India dynamics.

The manufacturing base in China was largely the result of the invigoration of the economy after the 1978 reforms, with the focus on attracting foreign investments, especially in the coastal provinces. Along with the aim of getting foreign capital, the Chinese diaspora along with businesses based in Taiwan and Hong Kong, were also targeted of these investment policies.

Over the years, the rise of the Chinese economy was on the wings of the industrial production and development. While the bulk of heavy industry is under State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs), an increased proportion of manufacturing also falls in light and consumer-oriented firms, which are either private or joint ventures.

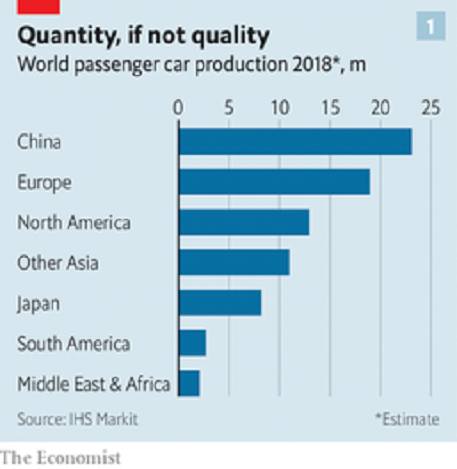

With deepening diversification, the industrial pace picked up in 1990s, with the development of automobile, electronics, and semiconductors, along with steel, cement, metallurgy and textiles. A cursory glance through the Indian market is enough to understand why the sobriquet ‘Factory of the World’ fits for China — such is the range of myriad consumer goods tagged as ‘Made in China’. Intricately connected with the global value chains, the manufacturing sector in China has often been considered robust.

This purportedly successful industrial development model has been offset with significant challenges. That the real essence of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was to find a fix for industrial and infrastructural overcapacities, is a well-acknowledged fact. With the rise of labour costs in the mainland along with the increasing worker protests, mainly in south China — the industrial hub of the country — due to despotic labour regimes in workplaces, manufacturers are grappling with either automating labour-intensive industries or move them to newer locations like Southeast Asia.

Further, the US-China trade war over the last one year has compounded in the slowing of economic growthresulting in the shrinking of the manufacturing sector. In fact, the trade war has also impacted the Made in China 2025 project, at least in terms of its active pronouncements and projections. These need to be contextualised while probing the dynamics and possibilities for China’s manufacturing sector to make forays in India.

There has been a spike in investments by Chinese companies in electronics (mainly mobile phones), home appliances, and automobiles, along with the tech sectors. The lion’s share of Chinese investments in India are private companies, thereby highlighting the reticence towards big ticket SOEs, and dawning the realisation that a good amount of such partnerships take place outside the purview of government-to-government engagements. However, these partnerships and investments are not necessarily the markers for the whole manufacturing sector, as there exist multiple humps on the road for both countries.

The increasing clamour among sections of the Indian business and political elite —enamoured by the glitter of China’s advancement —to ‘transplant’ the Chinese model in Indian settings, is oblivious to the inherent problems on both sides. The avowed ‘win-win’ as often bandied by the Chinese doesn’t translate into reality when it comes to technological transfer or knowledge sharing. Doubts exist in the count on employment creation, as Chinese enterprises abroad mostly seek have technical and supervisory/managerial personnel only from the mainland, thereby hiring local workers only for other routine and auxiliary tasks. This is often justified in the name of ‘work culture’ and ‘efficiency’.

Further, they view the regulative environment, with complex labour laws, discouragingly. The suppression of labour rights, is an inherent part of the ‘Chinese model’, and is even visible in subcontracting firms, as illustrated by developments at this phone manufacturing facility Delhi NCR; the export of this exploitative model is well documented in Southeast Asia. Clearly, there are enough warts are always cheek by jowl with the gloss.

Even as speculations continue on the enduring nature of China-India relationship amidst the Mamallapuram pit stop, we can be pretty sure that there is still a long way to go and multiple hoops to climb before the Chinese manufacturing sector can both meaningfully and substantively, shake hands with India.

Originally Published as Entry of Chinese manufacturing in India is a bridge too far in Moneycontrol.com, 9 October 2019