Mahesh Kumar Kamtam, Research Intern, ICS

The recent crisis in the South China Sea erupted in December 2019, when a group of nearly 30 Chinese fishing vessels, accompanied by the Chinese Coast Guards (CCG) intruded the “exclusive economic zone” (EEZ) of Indonesia around the Natuna Islands, a part of the sovereign rights guaranteed by the “United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea” (UNCLOS). China’s aggressive posturing in the South China Sea, accompanied by its large fleet of fishing vessels and maritime militia, brings new challenges to the region and the sustainability of South China Sea.

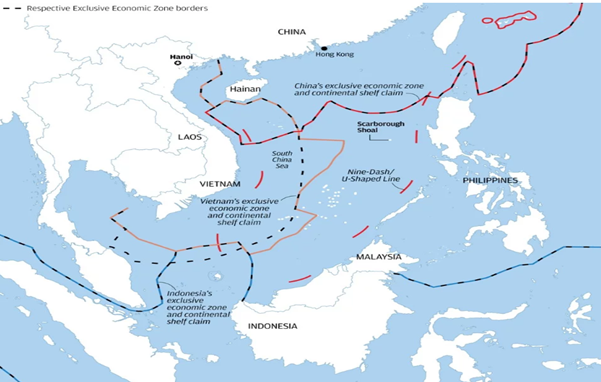

South China Sea has been at the centre of dispute since China began asserting its sovereignty over the entire sea as part of its historical claim of the “nine-dash line”. This claim not only makes it an expansionist power but presents a challenge to the sovereignty of the neighbouring coastal states with overlapping jurisdiction (see the map below). The Natuna crisis and China’s aggressive postures has irked the eye of many ASEAN member states. Nevertheless, I would argue that the crisis presents not only a security threat for the neighbouring coastal states but also challenges the sustainability of the entire South China Sea ecosystem.

Source: South China Morning Post

The South China Sea dispute must be viewed from the perspective of fisheries development and the conflict for fishing grounds in the region. A report by the Centre for Strategic International studies (CSIS) has shown that the region is dangerously overfished and over-capacitated with the fishing boats. For instance, the report cites a paradoxically worrying trend with South China Sea accounting for 12% of the global fisheries and more than 50% of the gross fishing boats of the world present in the region. Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) images captured by Asia Maritime Initiative depict this trend in the region (see image below). This shows that there is sheer overcapacity in the region in terms of fishing which has further led to aggressive behavioural tactics by countries involved in the South China Sea dispute.

Source: White Shipping Data, Asia Maritime Initiative

Tactics to intimidate the fishing community are adopted frequently by the CCG in the region to deter the non-Chinese fishers from fishing in the South China Sea region. Chinese fishermen, with the support of CCG and Chinese Navy, have also displayed aggressive behaviour in the cross-fishing activities in the disputed waters. One of their tactics includes ramming foreign boats and sinking them. For instance, a Filipino boat was sunk by the Chinese fishermen leaving 30 Filipino sailors at the mercy of others for rescue. Gregory Poling, Director of Asia Maritime Initiative describes this approach as a “constant exercise of low-intensity warfare”.

The Natuna crisis comes in the context of the departure of Indonesia’s Minister for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, Susi Pudjiastuti, whohas a strong track record of adopting tough policies on the protection of ocean ecosystem and the crackdown on illegal fishing activity in the Indonesian waters. With the departure of Susi, China is probably testing Indonesia’s ability to confront CCGs in the Natuna Sea. However, it is also aware that Indonesia stands as the fulcrum that connects the Pacific and the Indian Ocean. Therefore, it is seeking not to escalate the dispute further which can lead to a “crisis situation” in the region. Moreover, Indonesia has no conflicting claims in the South China Sea, unlike its neighbours.

China has for long claimed sovereignty over the entire South China Sea by arguing that “it is part of Chinese historic traditional fishing grounds” and expanded its naval presence through aggressive tactics. The Chinese Navy and the CCG are at the forefront by providing security and accompanying the Chinese fishing vessels, survey ships, and other mineral exploration activities in the South China Sea. Nevertheless, these activities are not confined to the “traditional fishing grounds” alone. Chinese ships have often crossed the established “nine-dash line” to either assert their control over fishing grounds by driving out foreign fishers or to test the neighbouring states’ potential and their capabilities in handling the crisis in a “matured” manner. Both the tactics are working in China’s favour to steadily extend its influence in the region.

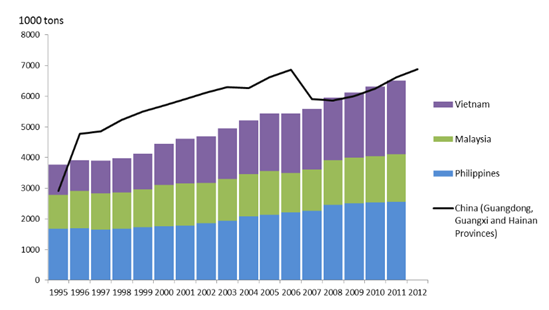

Chinese activities in the South China Sea have expanded in the recent past with an expansive military build-up, transforming the “ecologically fragile coral reefs” into a military outpost in order to establish their continuous presence in the region as a strong naval power. The modernization of the Chinese Navy and the inclusion of the indigenously built aircraft carrier, “Shandong” is an example of China’s growing capabilities in the region and its quest to become a “naval superpower”. Nevertheless, the disrespect for international laws and non-compliance with international norms can have possible implications not just for the maritime security in the region but also severely affects the livelihood of fishing communities who are solely dependent upon the ocean resources. The data compiled on the marine fishery production in the region by the Pearson Institute of International Economics shows dangerous levels of fishing activity in the region (see graph below). The Chinese fisheries community along the coast, being overwhelming dependent on fishing as their sole occupation, has put China in a compelling position to venture into the extra-territorial waters of other countries.

Source: Pearson Institute of International Economics

So, where are we heading towards in the South China Sea dispute? It seems, for the time being, China is trying to carve out its extra-territorial geographical expansion through a multi-prolonged strategy, with CCG and fisheries at the forefront of China’s expansionist agenda. However, the military escalation and the disturbance to the ecological fragility in the region may bring many livelihoods to standstill, ultimately affecting the region’s ecology and economy alike. This presents a long-term challenge to the region that risks human security at the cost of national security. Countries in the region and especially China, should be cognizant of the consequences that follow. Therefore, countries need to redefine the concept of security in the context of growing livelihood challenges.