Raj Trikkha, Research Intern, ICS

Source: MarketingFuture

The rise in globalization and internationalization of trade has paved the way for e-commerce to expand from within nations to across the globe. This type of e-commerce is called cross-border e-commerce (CBE), wherein, products or services are sold to buyers overseas through e-commerce websites. The extent of globalization is such that the annual growth rate of CBE, which is 17%, has surpassed the growth rate of overall B2C e-commerce, which stands at 12%.

Cross-border e-commerce in China began in 1998 with a few foreign trading companies tapping into the latest internet technology to carry out their sale activities. The year 1999 marked the birth of the company which changed the face of Chinese e-commerce. Alibaba.com, established by Jack Ma started out as a B2B portal that facilitated between local factories and overseas companies. In the mid-2000s, as more Chinese people went to foreign nations for work or studies, a new profession emerged, called DaiGou (代购). DaiGou refers to transactions where Chinese nationals who reside abroad sell foreign products to people in China with a little markup. They used various platforms like Taobao.com and WeChat. DaiGous for a long time filled the demand gap and still continue to conduct purchases online.

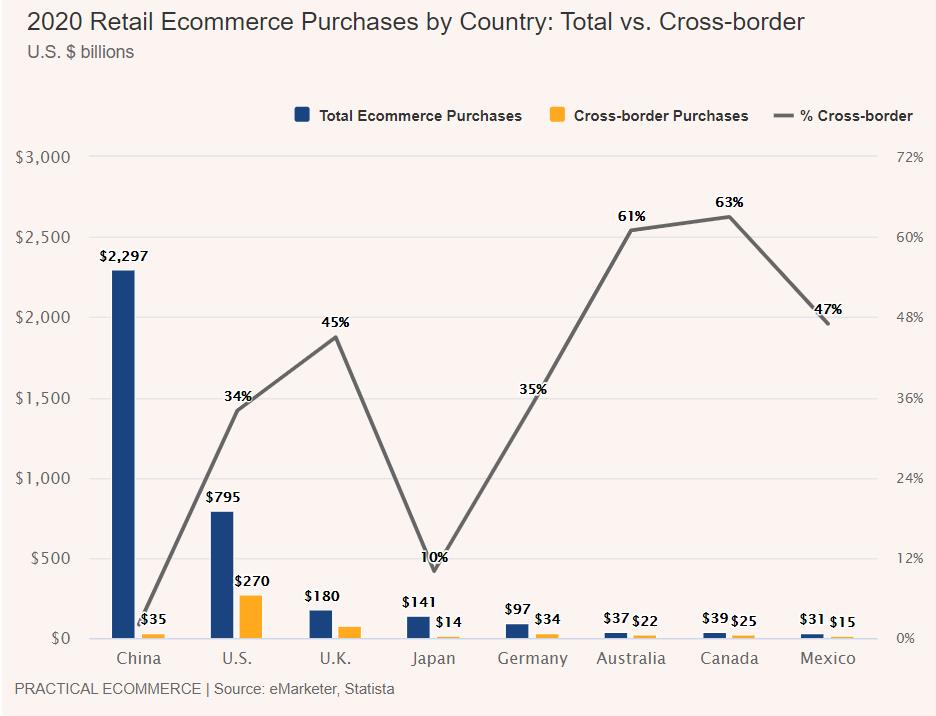

Since these types of transactions started to gain popularity and demand, companies like YMatou.com entered this market in 2009. CBE in China started to grow remarkably from 2013. This happened due to the vast acceptance and usage of smartphones. This made it easier for companies to reach consumers and for the consumers to avail their services. Between 2014 and 2015, over 5000 CBE startups were established in China involving Kaola.com and Vip.com. Today, the biggest e-commerce market in the world, China, has $34 billion worth of purchases in the CBE market (as of 2020). Though, in comparison with the U.S. (34 percent) and U.K. (45 percent), it consists of a mere 1.53 percent of its total e-commerce sales. This implies that there is still a lot of potential for the CBE market to grow in China.

Source: Practical E-Commerce

Although the market was growing and becoming an essential part of the technology-driven economy, the sustainable development of the industry required the supervision of laws and support of policies. Thus, starting from 2007, various government agencies released policies and recommendations to promote CBE in China. Subsequently, in 2014, China through the General Administration of Customs issued a new set of regulations pertaining to CBE. This was the first time that China officially accepted the CBE model. This opened up many opportunities for foreign firms wanting to sell their goods in China. As a result of increasing online sales by retailers, recent modifications in the CBE regulations were introduced on 1 January, 2019, to make them more robust.

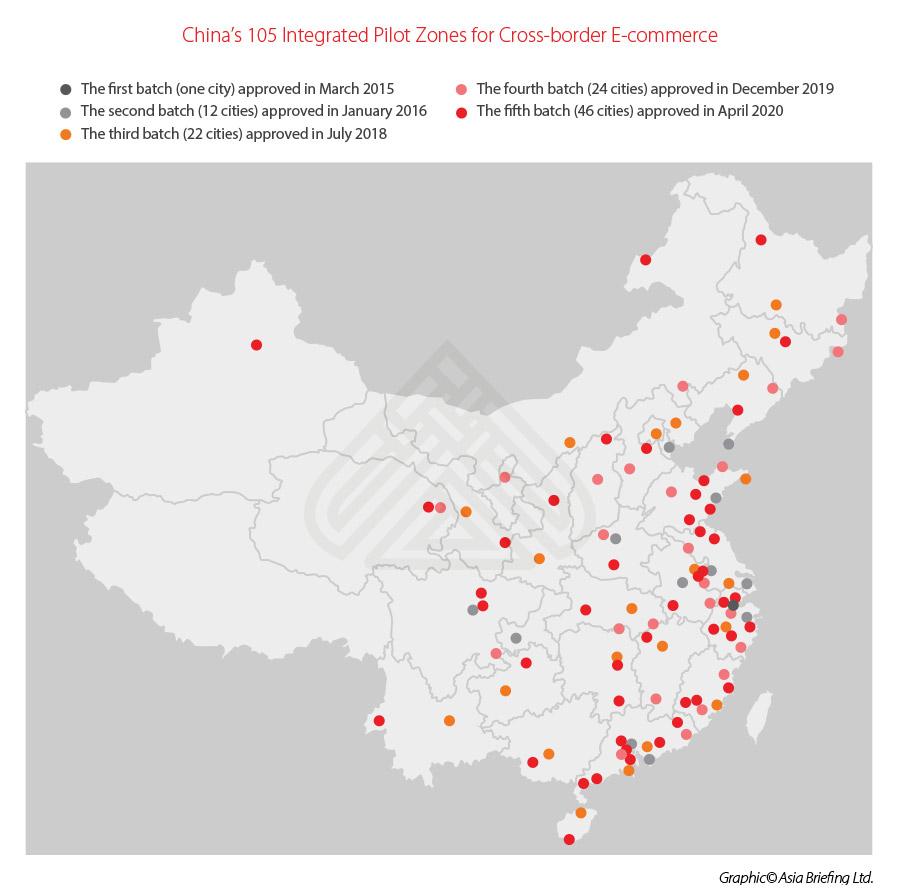

These schemes eased the process to a huge extent. Among many things, they lowered down the labour and logistics costs, streamlined the product return process, and announced the establishment of 46 additional cross-border e-commerce comprehensive pilot zones. Streamlining the return process enabled companies to ship goods in bulk to Chinese warehouses even before selling them to the customers, while more pilot zones meant that companies will have more areas where favourable tax rates are levied.

Source: China-Briefing

The new policies have had a positive impact on the industry. The first three quarters of 2020, show an increase in CBE retail imports by more than 17 percent year-on-year, according to customs data. Cross-border e-commerce in China is growing at a fast pace. Even during the pandemic era, the CBE sector in China brought 31.1 percent of its foreign trade. CBE has become an essential aspect of China’s foreign trade. In 2020, over 10,000 traditional foreign firms went online for the first time. Many experts believe that CBE will continue to thrust the foreign trade in China as the market is still less-tapped and the policy incentives are yet to be yielded.