Amitava Banik, Research Intern, ICS

China’s progress in manufacturing

China is considered as the world’s manufacturing powerhouse. China had been successful in building infrastructure supporting world corporations to make their products in the country. Over time, the world’s leading companies have shifted their manufacturing assembly lines to China. Also, the home-grown manufacturing industry in China is itself quite big. China is successful in manufacturing and exporting a whole range of products from simple electronics to complex machineries.

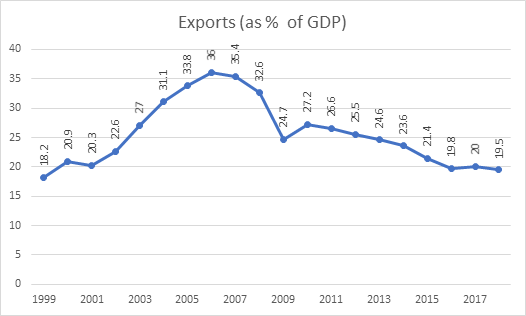

According to Yue and Evenett (2010), China attracted huge FDIs between 1979 to 2007 of which 70 per cent went to the manufacturing industry. The concentration and development of the global value chains of all industries, including the high-tech industry, on the eastern coast of China have boosted the country’s exports, resulting in the “Made in China” phenomenon.

Multinational corporations such as Siemens have set up facilities for assembly and manufacturing of many of its products including high-end medical equipments such as CT Scanners for their South Asian market in China, taking advantage of low manpower cost and good connectivity networks. A world-renowned instrumentation company such as Yokogawa of Japan, manufactures and exports their meters and oscilloscopes from China. The Chinese are considered to be good with reverse engineering capabilities, which have helped grow a lot of domestic manufacturers across industrial sectors.

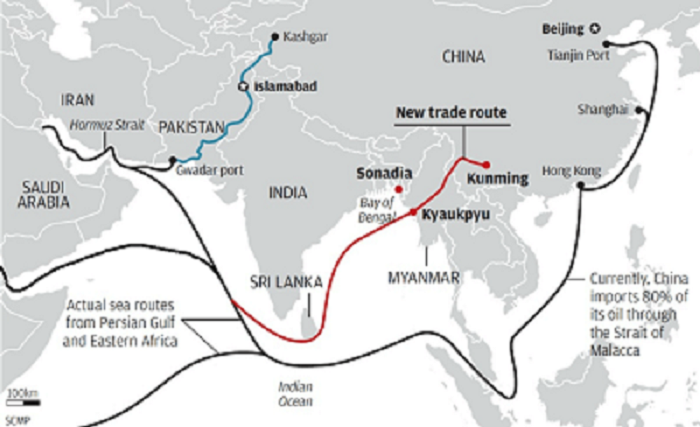

China’s market for capital goods and spares in Eastern India

The Chinese machineries and capital items occupy the top of India’s list of imports from China valued at US$ 19,103(2019-20). Unlike China, the global multinationals are more focused on making India a marketing hub for catering to the huge domestic market of India and South Asia rather than India being a global manufacturing destination. Thus, India’s manufacturing capacity for capital goods like other high technology products is low.

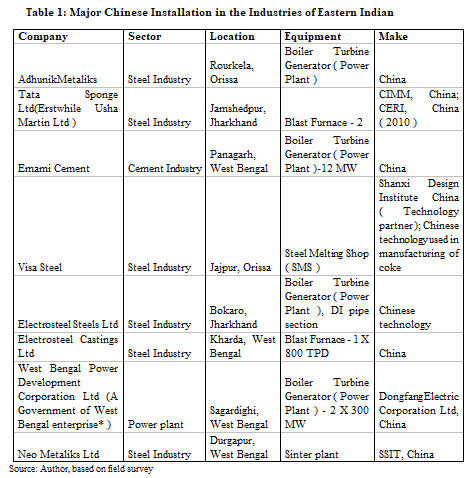

In Eastern India, where there is dearth of both capital and new industries, China has successfully filled the vacuum to some extent with its cheaper and competitive products and industrial solutions. According to a survey conducted by the author, traders and businessmen are of the view that there could be further enhancement of Chinese market in this part of the country if the Chinese companies could set up manufacturing and assembly lines for their products – both capital goods and spares in Eastern India. China has made considerable inroads into the industrial market in Eastern India both for high value capital goods as well as low value tools and spares. However, there is dearth of specific data on import of capital goods and spares parts from China by the industries of Eastern India, so this assumption is based on practical experience and field survey as illustrated in Table 1. According to some of the users interviewed from these industries, the satisfaction level of the industrial customers and the value for money proposition is good for Chinese products and their installations. The traders interviewed are of the opinion that easy loan and financial credit facilities are available for buying Chinese machineries. Companies such as Donfang Electric Corporation doing power projects have also set up offices in Kolkata to oversee their projects, marketing, and customer services, etc. The traders are vocal about dealing with China’s ease of doing business. According to them, it is easy to get dealership of Chinese companies and start doing business with them, and Chinese manufacturers are also prompt in responding to trade or dealership enquiries.

Eastern India is primarily a mineral rich belt of India producing steel, ferroalloys, power, etc. Earlier, most of the installations in old plants had been of Russian, US or German technology, but now most of the plants, particularly those built on private investments are using Chinese technologies (Refer Table 1). Even in many of the tenders called by the central and state PSUs*, Chinese companies are the lowest bidders and many of them are ordering Chinese products.

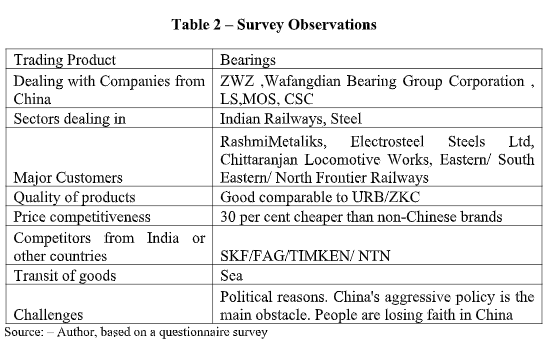

Just like industrial installations of capital goods in Eastern India, Chinese manufacturers have made considerable penetration into the market for low-end manufactured products, tools and spares. The trading communities in Kolkata and other places import Chinese products at lower price and sell them in the market at a premium and make considerable fortune. The result of the survey of a leading bearing trader in Kolkata is put up in Table 2.

Present Situation

The military standoff situation like the recent Galwan Valley clashes and its aftermath creates anxiety among the trading and industrial community, which affect business sentiments. As the Chinese influence is currently highly embedded in Indian economy, trade and commerce, complete decoupling may be expensive for India especially in the present Covid-19 pandemic scenario. However, though decoupling is tough, at the same time it is not possible to entirely ignore border and security issues in the face of economic or business considerations. Thus, India needs to look at economic growth with leverage on China.

Conclusion

Chinese economy (about US$ 14 trillion) is much bigger than that of India (about US$ 3 trillion). India is home to 1.3 billion people (17 per cent of world population) but has only 3-4 per cent of the world GDP. Although the two countries try to co-operate on several international forums such as WTO, BRICS, G20 etc., strategic rivalry is visible. This shows that while there is an understanding on many common matters of concern, the two economic giants sharing a common boundary and geopolitical and historical landscape are often at loggerheads on issues of diverging interests, geopolitical and economic ambitions.

In view of the evolving world order during the pandemic, several multinational companies are looking to relocate their manufacturing facilities out of China. It may be an opportunity for India to pitch in and fill the void by offering incentives to these corporations as well as to Indian corporates for setting up more manufacturing facilities in east and northeastern parts of India, and other untapped industrial belts. This may also help in developing these deprived regions as new industrial pockets. If this happens, it would lead to overall growth and development of these regions and augment the value chains for the industries.