Hemant Adlakha, Honorary Fellow, ICS and Associate Professor, JNU

The Communist Party of China has allegedly forbid state-controlled media from choosing sides between Trump and Biden. The leftist intelligentsia had hoped to see hostile “mad king Trump” continue for four more years. The “nationalist” left is also accusing the pro-reform, pro-market neoliberal “right” of pretending to be blind to the fact that “Sleepy Biden” will bring more trouble for Beijing.

With president-elect Joe Biden not declaring himself winner yet and President Donald Trump refusing to concede defeat, China’s pro-US elite too appears to be confused and divided. Unlike what the international press would want us to believe, that is, overwhelming opinion in China does not see a “Red” or “Blue” White House would bring a turnaround in the worsening Sino-US relations. The truth however is the continuing unclear verdict of November 3 vote is causing ugly ideological spat in the open among the Chinese elites. In the ideological battle being fought on the country’s “lively” social media, there are the anti-US leftists on one hand and the pro-US rightists on the other. The two rival groups are popularly referred to as fanmei and qinmei in Chinese respectively.

From the outset, the leftists in China firmly maintain the American elite will never be friendly towards China. A blog post under the name Weile zuguo qinagsheng, or “For the Prosperity of the Motherland” recently declared, “Given the US imperialism’s aggressive character and its natural tendency to loot and plunder, the United States cannot be friendly with China. The United States will always look at China as an enemy and it can never cooperate with China. The US and China can never enjoy a ‘win-win’ relationship.” Therefore, most Marxist scholars in China uphold the view that a more internally chaotic America augurs well for China. No wonder several leftist commentators have welcomed the turn of events in the past couple of weeks making it clear that President Donald Trump is refusing to accept his electoral defeat and is actively engaged in a coup to overturn the elections and establish “individual” dictatorship.

A recent article in one of the country’s leading leftist current affairs and news platform claims, as compared to a stubborn, inveterate and incorrigible Donald Trump, the Democrats are out-and-out believers in exporting their ideological doctrine. “Scores of NGOs, public intellectuals in China are receiving funds from the US Democratic Party. For example, ‘Wildcat’ – a fake women’s rights blog on Weibo has fallen silent following the closing down of the US Consulate in Chengdu. Why? Because its source of funding has been cut off,” the article proclaimed. Further, the leftist commentators are also pointing out, with the prospects of Biden sure to become the 46th president of the United States, several Chinese public intellectuals – a euphemism China’s leftist scholars despicably employ to describe “pro-US” intellectuals – who had been quiet in past four years have suddenly resurfaced on the Chinese social media, thanks to Trump’s foreign policy of “isolationism” and massive funds cutting to pro-democracy intelligentsia abroad.

China’s leftist intelligentsia, which disdainfully lambasts those pro-America Chinese who are keenly following this years’ US presidential election, broadly tags them into three types: first, large majority who look at the US election as a source of great amusement. They can easily switch sides from supporting Trump or Biden. It really doesn’t matter to them who eventually enters the White House. What they need to do is to pull a chair to sit, spread enough munchies and beverages in front of them and watch the election ‘drama’ being played out on TV. What they hope to see is Biden winning with a thin margin and Trump adamantly refusing to step down; the white supremacist Trump supporters thronging the streets wielding guns and swords, and Biden fan-followers not far behind. These Chinese are most happy to see 50-50 election outcome tearing the United States apart.

Of course, a small faction among this group would love to see Trump emerge as the winner. This group subscribes to the view that to oppose China has become the US national policy and to contain China is the consensus position of both Democrats and Republicans. But Trump being more blunt and ruthless, like the past four years have shown, another four Trump years will be a good wakeup call to all those “confused” pro-US Chinese. At the same time, there is another small faction who thinks the Democrats, under the curse of “not fully advocating anti-China policy,” will be relentlessly egged on by the Republicans and therefore will be forced to implement a more hardened “anti-China” policy. As a result, the pro-US Chinese will be forced to turn against whoever leads the US administration.

The second types are those who according to the leftists are big fans of President Trump. The leftists accuse them of “living in China but dreaming of America.” For these Chinese, Trump is almost a semi-god or a hero. They have no qualms in their motherland going to tatters while they worship the Unites States. Furthermore, they are in awe of Trump not only because he is being tough on China but because Trump’s protectionism and “isolationist” policies are helping America regain its core values and are rescuing both the United States which is already in decline and rescuing the humankind. In other words, Trump is the only saviour of humanity.

There are not many such people in China. They are easy to identify. They include pro-market “liberals” such as Caixin editor Hu Shuli, the Beijing-based think tank Charhar Institute, economist Justin Lin Yifu, and the author of Wuhan Diary fame Fang Fang, etc. and several other elites from culture and art circles. But they are harmless.

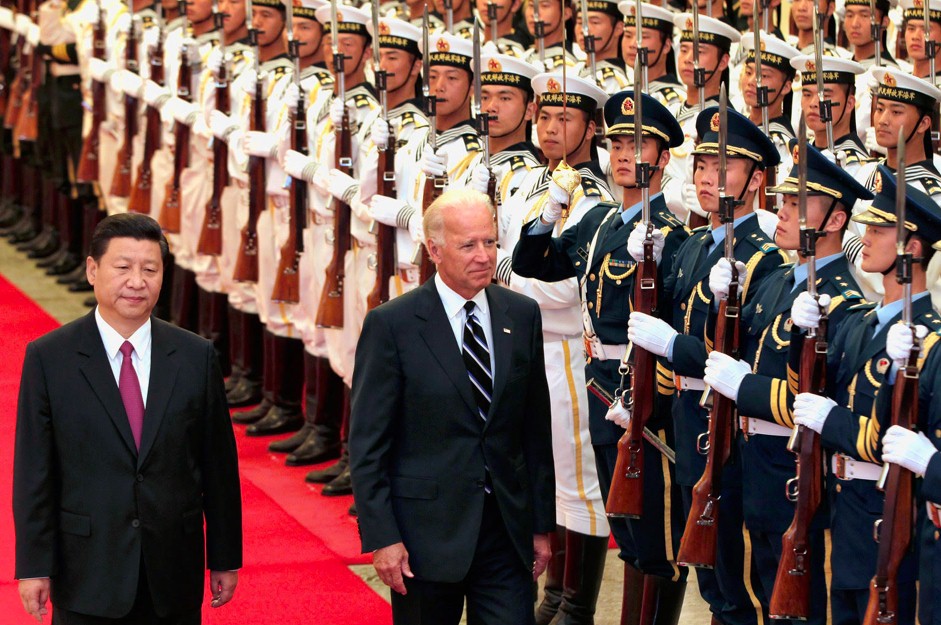

In the third category are those whose hope for the reversal of currently hostile US attitude towards China rests on Biden. In this group, one faction seriously thinks China’s national strength is lagging far behind the US. For they believe though China and the US are destined to collide but because the enemy is stronger it is only wise on China’s part to maintain policy of appeasement at least as long as China grows in strength. Another faction in this group of US supporters believes the past four years under the Trump administration have been rather “abnormal.” They consider the four years under the second term of Obama presidency – called “Chimerica,” as a normal phase in China and US bilateral relations.

Making a dig at the Global Times editor, Hu Xijin, the leftists claim he couldn’t even wait for the final outcome of the vote count and used a fake Twitter account to make an appeal to Biden to revive the Sino-US “marriage.” A couple of weeks ago, Hu Xijin found himself at the receiving end of a fury of attack by leftist scholars for inadvertently stating “Reform and Opening Up is Chinese people’s natural choice.” Besides, the so-called “US worshippers” – as the public intellectuals such as Hu Xijin in China are called by the leftists, are also drawing flak from the leftists because of their feigned “ignorance” of not seeing Democrats as the bigger devil as compared with the Republicans. Unlike Trump who ensured America’s global hegemony accelerates into eclipse for reasons too well known to all, Biden is both a true believer of “liberal multilateralism” and “Cold Warrior.”

Finally, convinced that Biden’s core foreign policy team comprises of Obama “old hands,” the leftist Chinese commentariat no doubt apprehends continuity of Obama administration’s legacy under Joe Biden, especially in the US policy toward China. China International Relations University Professor Chen Zheng, an influential foreign policy analyst recently wrote: “Although Obama administration did not openly declare China as the US strategic enemy, but Trump’s anti-China policy has been built on what he inherited from the Obama White House, that is, the failure of the US national strategy to continue to ignore ‘a rising China’.” In the last phase of the Trump presidency, the US not only openly and publicly started addressing the CPC-led China as the strategic enemy of the United States, but the Republican Party’s extreme right-wing elite was already pitching for US-China “decoupling” and pushing the world’s two largest economies into “Cold War,” Chen Zheng added.

To conclude, China’s leftist intelligentsia appears to be spot on in their assessment that in recent years – as also during the COVID era – the Republicans and Democrats as well as the US political establishment have struck consensus only on one issue, i.e., how to prevent China from rising. Joe Biden will be too happy to carry forward the consensus, the leftists in China are telling us.

Originally published as Chinese Public Opinion Split over Biden by Nepal Institute of International Cooperation and Engagement (NIICE), Kathmandu on December 3, 2020.