Anushka Maheshwari, Research Intern ICS

Source: South China Morning Post

The Chinese economy, due to the strict measures adopted by the government to curb the spread of the Covid-19 virus, is back on track, with output back to pre-pandemic levels and a surge in credit activity. China’s financial regulators are having a hard time containing risks at home while limiting disruptions from abroad as the economy is opening to foreign investment. The fear of missing out has stoked the investors’ expectations and many people are now buying property for investment or speculative purposes, which Guo Shuqing, chairman of the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission, termed as “very dangerous”. The household debt in China had reached 150 percent of its disposable income in December 2020 driven by a rise in property prices and seems to be concentrated among the millennials. The youth of China is clearly banking upon the government to sustain this growth in real estate prices, but a major portion of this debt is financed by shadow banking. People’s Bank of China (PBOC) defines China’s shadow banking as “credit intermediation involving entities and activities outside the regular banking system”.Since this sector is outside the formal banking sector, it lacks a safety net that comes from being financially backed by the government through deposit insurance publicly guaranteed or ‘lender of last resort’ facilities by China’s central bank. This raises an important question: Is China on the verge of a financial crisis like the one faced by the US in 2008-09?

China escaped the 2008 financial crisis primarily because of its booming domestic market and little exposure to the overseas market for wholesale funding. But the contraction in capital inputs through foreign direct investment during the crisis and fall in exports made the government announce a $586 billion stimulus package to provide a boost to the economy. Major infrastructural activity, constituting 72 percent of the package was undertaken, and only 30% percent of this was financed by the central government. The rest had to be funded by the local governments, and since they couldn’t borrow funds themselves, local government financing vehicles had to take on debt on their behalf from banks. But banks had severe restrictions in terms of lending such as caps on lending volumes imposed by the PBOC, mandatory bank loans to deposits ratio, restrictions on lending to certain industries, reserve requirements, among others. Due to this, shadow banking activities grew along with an increase in fixed investment, driving economic growth but at a high cost, so much so that the corporate debt to GDP ratio reached a record 160 percent in 2017 as compared to 101 percent 10 years prior to it.

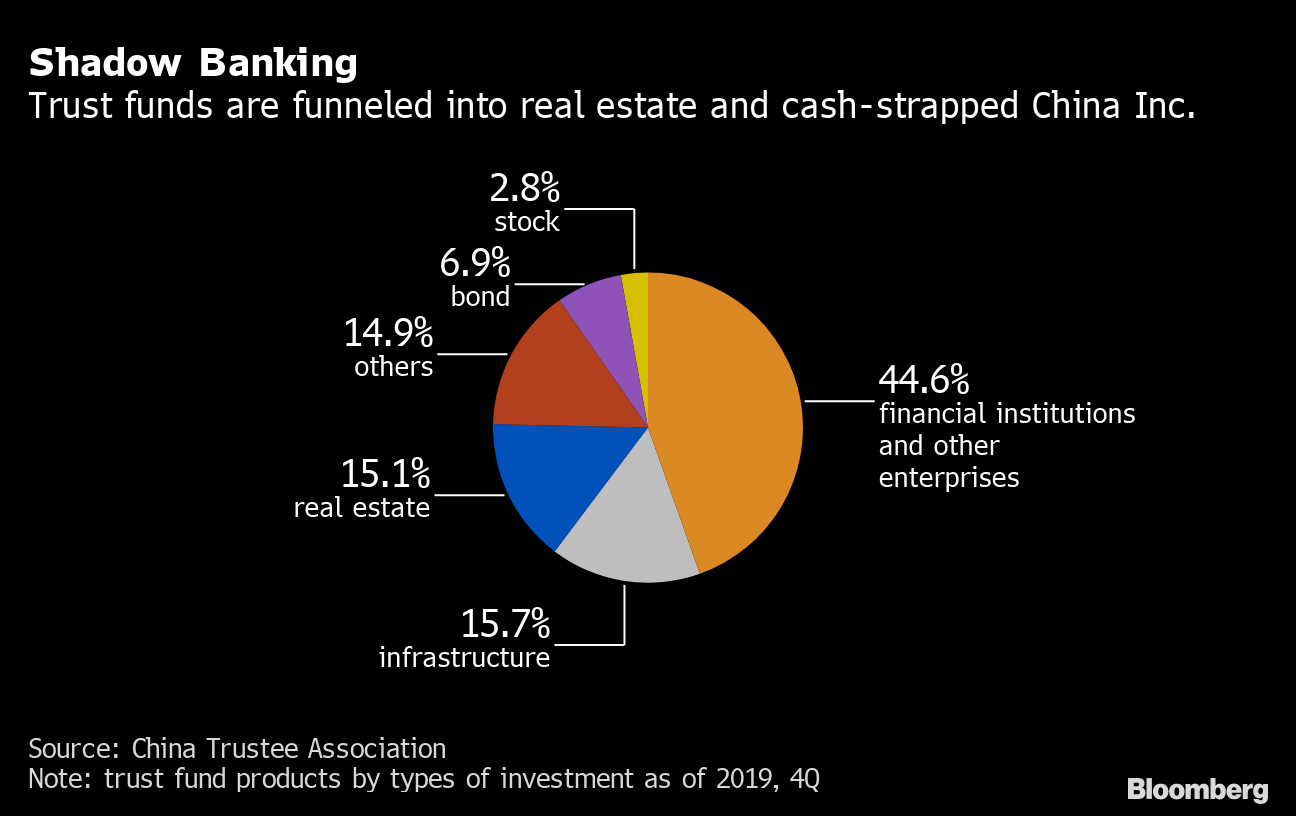

The Chinese leadership claimed that it had successfully defused the housing bubble that had formed in China by the end of 2014 due to these shadow banking activities. So, in order to uplift the dampening economy in 2015, it eased restrictions on second-hand home purchases and the property market since then has been booming, with more households buying houses and property developers borrowing more to engage in construction activities. There are many factors causing an increase in shadow banking activities, which in turn contribute to the growing real estate bubble. Firstly, Chinese authorities are trying to sustain high GDP growth rates through credit borrowing which puts strain on financial institutions of the country. Secondly, zombie companies that have little to no productive use, are borrowing more and more simply to meet their current obligations. Thirdly, many state-owned and private companies in China have property subsidiaries, and property loans made to these subsidiaries are sometimes presented in the books as going to the parent company. This results in the share of property-related debt being much higher than what is available in the official data. The overall impact was that the amount invested in Chinese housing hit $1.4 trillion in June 2020, while the total value of houses and developers’ inventory, according to a Goldman Sachs report, had reached $52 trillion in 2019.

Source: Bloomberg Quint

The shadow banking system in China works independently of its monetary policy, amplifying increases in the money supply but working opposite when the restrictive interest-based policy is imposed. Thus, it can be inferred that in spite of the Chinese policy changes to curb the real estate sector, the negative role of shadow banking is why the bubble continues to build. President Xi Jinping’s statement in 2017 that “houses are built to be lived in, not for speculation” clearly indicates that the PLA government is sensitive to this issue. The government in China has adopted stringent measures to stop the rise in property prices over the past few years, and the latest mandate in August 2020, restricted credit supply to both developers and investors. These new regulations that mandate all lending institutions to decrease the quantity of loans given to this sector are going to stay in place until the real estate cools off. There are two forms of shadow banking in China, one is the channel business of Chinese banks that hide some of their lending activities to keep them outside the purview of the auditors and regulatory bodies. The other is P2P(Peer-to-Peer) lending platforms like trust companies, factoring companies, etc. In order to contract both these forms, the Supreme Court in China has lowered the interest rates on microlending, which will make it unprofitable for lenders while the CBIRC(Chinese Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission) has forbidden trust companies to finance developers that do not meet the necessary requirements of shareholders and capital or lack necessary licenses.

The PBOC has significant control over lending activity in China as compared to the independent decision-making possible in the U.S. markets, which implies that the situation in China is more stable. There are many structural differences between the shadow banking systems in China and the United States, such as in China, market-based financial instruments do not play as significant a role as they do in the USA. Also, in China, smaller banks went off-balance sheet as they were constrained by liquidity requirements as compared to the larger banks in the US that were constrained by capital requirements. All these factors considerably lessen the chances of a financial crisis like that of 2008-09. Also, the Chinese real estate market has higher-than-normal down payments, sometimes as high as 40-50 percent of the transactions as compared to the 10-20 percent in most western markets. This implies that the debt to transaction price ratio is low, which discourages people from the lower socioeconomic strata of Chinese society to purchase high-priced properties, thereby reducing the risk of defaults. The PBOC and the CBIRC stepped in to take over the Baoshang bank when it collapsed in 2019, whichhas both positive and negative implications. On one hand, it indicated that the Chinese government may intervene in case of any crisis-related situations caused by defaults in the shadow banking sector, but on the other hand, it may also encourage risk-seeking behaviour from creditors depending on the government to back the financial system. The Chinese government is caught between trying to curb shadow banking activity in order to reduce system risk in the country due to the real estate bubble and ensuring liquidity in the economy. Thus, although the possibility of a financial crisis is low, China does need to reduce risks posed by its shadow banking sector and ensure financial stability.