Hemant Adlakha, Honorary Fellow, ICS

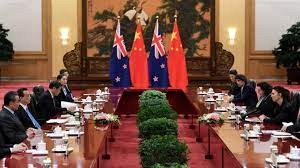

President Xi Jinping and New Zealand PM Jacinda Ardern

Summary: Neither did Trump nor will Biden, the US is not going to specially reward any of the “Five Eye Alliance” allies if they out compete each other against China. Look at how New Zealand is giving Australia a lesson, Chinese scholars are saying.

Trump is gone. So is Mike Pompeo – the “crazy” rabid anti-China former Secretary of Defence, who according to Chinese international relations experts miserably failed in rallying together the US “Five Eye Alliance” partner countries against China. With the return of Biden to the White House after four years as the President of the United States, Australia is already paying a heavy price for blindly following Trump-Pompeo anti-China policy. This is what a recent Chinese article claimed and described Australia’s predicament in a rather telling joke: To push its anti-China drive, the US called on its allies to come up on the frontline and take lead. The US said: You lead; the UK said: you lead; Germany, Japan and New Zealand one by one too said the same. However, when its turn came, Australia, beaming with enthusiasm replied: Okay, I shall lead! But soon Australia was seen running back towards the allies “crying” and complaining: “He is beating me! He is punishing me!” Alas, no one came forward to help or rescue Australia.

As it turns out, according to some Chinese analysts, it is New Zealand which is “teaching” Australia on how to get along with China. Recently, concerned that its tiny neighbour has been “changing its priorities a little bit” and “not fully committing itself to Five Eyes and trying to keep an eye elsewhere,” the Australian Prime Minister Morrison told Sky News on February 1: “The Five Eyes is really important, and so are liberal market democracies… all of these countries need to align more… on security issues and intelligence” in opposition to “authoritarian” countries.”

New Zealand signs upgraded FTA with China on Jan. 26, 2021

What is FVEY?

The origin of the Alliance, also called FVEY, can be traced back to the post-WWII period when the multilateral UKUSA Agreement was signed for joint cooperation in signal intelligence. During the Cold War, the five countries developed a surveillance system called ECHELON to target monitoring the communications of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc countries. Following the end of the Cold War, in the 1990s and in the following period, FVEY initiated ECHELON system expanded it surveillance on the “war of terror” and soon included widespread spying on the citizens of even the alliance partner-countries.

More recently, since early 2018, FVEY along with three more countries – France, Germany and Japan – introduced an information-sharing framework to counter threats arising from foreign activities of especially China, and also Russia.

China takes a stab at one of the Five Eyes Alliance country

It is worth paying attention how the controversial arrest of Meng Wanzhou, a top executive and daughter of Ren Zhengfei, Huawei CEO, in December 2018 at the Vancouver International Airport was carried out. According to the Chinese government, the entire operation was conducted based on the information supplied by the world’s oldest intelligence alliance, the Five Eyes.

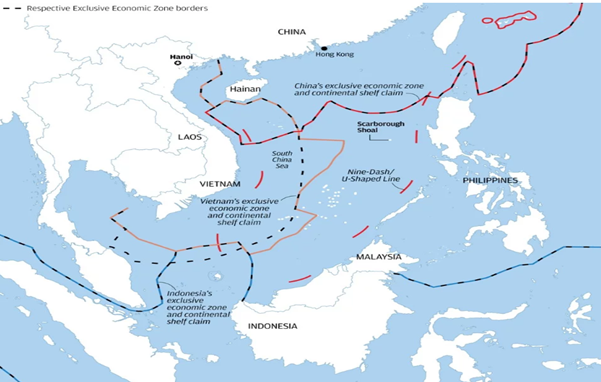

The US push to allies in Indo-Pacific and SCS

Now, pumped up by “anti-Xi Jinping” and “anti-CPC” Mike Pompeo, Australia as one of the FVEY countries, decided to step up the US anti-China campaign in the region. This led to more and more Chinese commentators dig out the recent history of Australia’s increasingly over- enthusiastic and proactive frontline role against China in the Asia-Pacific and in South China Sea. Broad consensus among China’s strategic affairs circles is, beginning with the US “re-equilibrium strategy” during the early 2010s under President Barack Obama, Washington has greatly expanded its military presence in the Asia-Pacific (now Indo-Pacific) region.

NZ Trade Minister Damien O’ Connor

In this backdrop, it is pertinent to refer to what Admiral Charles Richard, head of the US Strategic Command, which oversees nuclear weapons stated recently. Reacting to last year’s China’s military report, Adm. Charles had said at the Department of Defence press briefing on September 20: “[China] military report is an explanation in terms of what China’s overall strategy is. And China in particular is developing a stack of capabilities that, to my mind, is increasingly inconsistent with a stated no-first-use policy.” A WeiBo blogger, Bu Yi Dao, whose write-up, like several other commentators perceived Adm. Charles’ above remark “a clear reflection of the US bipartisan elite consensus behind increased provocative military exercises in SCS, along with some allies in the region, aimed at preparing for an attack on China.”

Australia miffed over New Zealand’s leaning towards Communist China

Let us return to the Australia, New Zealand spat over China. During the past few years, under Labour and Liberal and/or right-wing nationalist alliances-led governments, both Australia and New Zealand have strengthened military ties with the US and have adopted more explicit anti-Chinese stance respectively. Some have even argued the two Oceania neighbours, like most Western countries, faced with the world economic crisis and exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, have increased their military spending and have allowed nationalism to go unchecked. It is in this context, New Zealand upgrading its “free trade” agreement with China last month, was seen both in Beijing and Wellington of added significance.

However, what triggered Prime Minister Morrison to warn “prickly” New Zealand “not to eye elsewhere” was the remark by NZ trade minister after the FTA was signed. Widely reported in Australia and New Zealand, Trade Minister Damien O’Conner – who is not particularly a leading light in the Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s second-term cabinet – with his spectacular jibe at Morrison, at once “stepped into diplomatic doo-doo.” Writing for the Lowy Institute’s the-interpreter, Robert Ayson awarded O’Connor both douze points and extra bonus “for telling Australia, a somewhat important partner, to follow New Zealand’s example in crafting a more positive relationship with China and for suggesting that Australia needed to show China some respect.”

Australian PM Scot Morrison

China having the last laugh

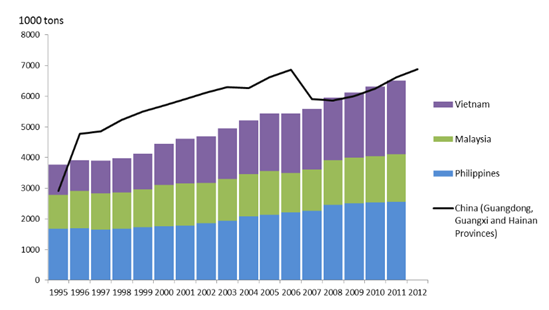

In China, commentators welcomed the FTA signed on January 26, especially in comparison with the deteriorating Sino-Australian ties. The agreement will remove or reduce tariffs and compliance costs on most forestry, dairy and other exports from NZ, while providing benefits for its education, aviation and finance industries. Moreover, several Chinese commentaries, in particular the strategic affairs experts, in the context of the FTA described New Zealand as the “last eye” among the FVEY countries. A popular military affairs blogger under the name Hou Sha, whose blog on Australia-New Zealand spat was picked up by multiple Chinese online news platforms and mobile news apps, including the influential leftist Utopia, even asked if the New Zealand Prime Minister Ardern’s praise for China in her curt reply to the Australian PM Scott Morrison had left the latter “red faced?”

Prime Minister Ardern had sought to distance herself from the controversy stirred up by her trade minister. However, with Australian Prime Minister Morrison taking up the issue with O’ Connor, Ardern disdainfully dismissed Morrison by saying: “I don’t necessarily take that same position in the way he’s [O’ Connor] presented it… In the same way we wouldn’t expect Australia to give too much commentary on our relationship [with China]; we shouldn’t be giving commentary on theirs.” Commenting on the controversy, The Guardian, in a report cited above, warned both Australia and New Zealand to be careful with China “attempting to drive a wedge” between the two members of the Five Eyes intelligence alliance.

Ground Zero for Chinese Influence

China’s hyper-nationalist Global Times, in an article “Why New Zealand and Australia’s relations with China are cases of ice and fire” published the day after the FTA, listed out three reasons why the two countries, both members of the Commonwealth of Nations and the FVEY, have such a huge difference in their relationship with China. Namely, First, New Zealand respects rules of the market economy and has reached consensus with China in promoting free trade; by contrast, citing “national security,” especially since 2018 Security of Critical Infrastructure Act, Australia has set limit on Chinese companies which has led to a sharp decline of Chinese investment in Australia. Second, Wellington doesn’t take sides between Beijing and Washington; whereas Australia has been acting as an anti-China vanguard for the US. Thirdly, New Zealand is relatively open toward the rise of China. It was the first Western country to have signed a cooperative document with China under the framework of the China-proposed Belt and Road Initiative (BRI); Australia is not only filled with hostility toward China’s rise, it has use legislative means to abolish the BRI cooperation agreement signed between China and its state of Victoria.

Another Five Eyes alliance joke which went viral on the Chinese social media recently, hailed New Zealand as its eyes wide open while ridiculing Australia for its totally blind eye!

The article is a modified version of the original article titled Beijing having the last laugh as Australia, New Zealand spat over China turns ugly published by modern diplomacy on 11 February, 2021