Bihu Chamadia, Research Intern, ICS

The new Hong Kong National Security Law (香港国家安全法 ) has caused massive controversy in Hong Kong as well as in the international community. On 21st May the Chinese authorities introduced a proposal in National People’s Congress (NPC) to enact the National Security Law. Further, on 28th May, the 13th NPC (人民代表大会), voted in favour of the National Security Law (NSL) for Hong Kong. The new law aims at tackling secession, subversion, terrorism and foreign interference, the details of which were kept under wraps until it was implemented on 30th June2020. A protest broke out in Hong Kong city on 1st July and several people were charged under the new NSL.

The NSL consists of a total of 66 Articles divided among six chapters. Some Articles are more important to look at, as they provide an overview of what awaits Hong Kong (香港) and anti-CPC Hong Kong citizens.

Article 12 of the Law states the establishment of a Committee for Safeguarding National Security, which will be under the supervision of and accountable to the Central People’s Government in Beijing. Although the committee will be headed by the Chief Executive, Article 15 states that the committee will also have a National Security Advisor, who will be designated by the Central People’s Government and shall be responsible for providing advice to the committee relating to its functions and duties. Article 14 states that the committee will work in secrecy and its decisions are not reviewable by the court. While Article 5 states that all persons shall be considered innocent until declared guilty by the judicial organ, Article 42 contradicts it by stating that no bail shall be granted to a criminal suspect or defendant unless the judge has sufficient grounds for believing that the criminal suspect or defendant will not continue to commit acts endangering the national security. Article 38 states that the law would be even applied to offences committed against the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) from outside the region by people who are not a permanent resident of HKSAR. Article 40 provides that the jurisdiction is in the hands of the Hong Kong authorities by default but it can be taken over by the mainland’s office for Safeguarding National Security. Further, Article 57 states that once in mainland, the processing and sentencing will be done according to the Chinese Criminal Law Procedure.

On the other hand, Article 60 provides complete impunity to the office and its personnel as they are not subjected to the jurisdiction of HKSAR while performing any act in the course of duty. The National Security Law has caused ripple effects not only in Hong Kong but in the international arena as well.

Hong Kong in Sino-US Relations

Sino-US relations have seen a massive downgrade since the Trump administration came into power in 2017. Human Rights and Trade have been a point of contestation between the US and China. Hong Kong has always acted as a geopolitical buffer state between China and the West especially for the U.S. Under the Hong Kong Policy Act of 1992, the U.S. had decided to maintain its favourable treatment, especially in the matter of trade, even after Hong Kong was reverted to Chinese sovereignty in 1997. The underlying condition for the preferential treatment was the autonomy of HKSAR. The Act also stated that “whenever the President determines that Hong Kong is not sufficiently autonomous to justify treatment under a particular law of the United States,” he is authorized to “suspend the favourable treatment.” In the wake of anti-extradition bill protests in 2019, the U.S. Senate and the House respectively passed the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act (HKHRDA) in November of the same year.

This indicated that the State Department would annually require to re-certify Hong Kong’s autonomous nature, in order to continue the so-called “special treatment” the U.S. affords to Hong Kong. It was a week after the National Security Law was tabled for voting before the NPC on 27th May, 2020 the U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo refused to certify the autonomy of HKSAR. On 28th May, the NPC passed the Hong Kong National Security Law. On 29th June, the U.S. Department of State ended exports of U.S.-origin defence equipments to Hong Kong. It also mentioned that U.S. will take steps to impose the same restrictions on U.S. defence and dual-use technologies to Hong Kong as it does for China. Mike Pompeo in his Tweet mentioned about the waning of ‘One Country, Two Systems’ (一国两制) and replacement of it with ‘One Country, One System’. As the Sino-US relations have already been in a tailspin due to the ongoing trade war and the COVID-19 impact, the recent issues have further exacerbated tensions in an already fragile relationship.

Sino-British Relations

Hong Kong has been a major component of the Sino-British relations. The recent move by the Chinese government has led to deterioration in the relations between two countries. Hong Kong was handed back to Chinese sovereignty in 1997 under the Sino-British Joint Declaration, 1984. Since then Hong Kong has been ruled under the framework of ‘One Country, Two Systems’, which is to continue until 2047. Under this system Hong Kong maintains a mini-constitution and enjoys autonomy on matters other than defence and foreign relations. On the National Security Law, the UK criticized China for breaching the ‘One Country, Two systems’ formula. On 11th June 2020, while presenting the 46th report to Parliament on Hong Kong, the British Foreign Secretary mentioned that China must respect Hong Kong’s autonomy and its own international obligations. Britain also mentioned that the Joint Declaration is registered with United Nations (UN). Thus, indicating its international obligations. On the other hand, China has mentioned that the Sino-UK Joint Declaration is unilateral policy announcement by China and not an international commitment.

On 1st July, Britain introduced a new

route for those with British National (Overseas) (BNO) status to move to UK.

BNO status holders refer to Hong Kong citizens born before 1997. The recent

announcement by the British Prime Minister Boris Johnson in the House of

Commons, extended the Right of Abode (ROA) to dependents of BNO passport

holders, giving way for millions of Hong Kong citizens to acquire British

citizenship. China’s Foreign Ministry criticized Britain’s decision and

mentioned that the offering of ROA to BNO status holders is a breach of the

terms of a memorandum offered by the UK to China in 1997.

China-Hong Kong Relations

Hong Kong maintains a democratic-capitalist system under the shadow of Communist China. It also enjoys certain level of autonomy on various matters and is governed by Hong Kong Basic Law. Article 23 of the law states that the HKSAR “shall enact laws on its own to prohibit any act of treason, secession, sedition, subversion against the Central People’s Government, or theft of state secrets, to prohibit foreign political organizations or bodies from conducting political activities in the Region, and to prohibit political organizations or bodies of the Region from establishing ties with foreign political organizations or bodies.”

Before the British handover of Hong Kong to China in 1997, China’s crackdown on the student-led democracy movement in 1989 created anxiety in Hong Kong regarding the handover and led to the political awakening of the population. In 1992, Chris Patten was appointed as the last colonial governor of Hong Kong. Patten initiated a series of political reforms designed to give the people of Hong Kong a greater voice in government via democratic elections to the Legislative Council (LEGCO).

When Hong Kong’s Democratic Party, led by barrister Martin Lee, routed pro-Beijing candidates in the 1995 LEGCO elections, Beijing denounced Patten and began a series of strong measures aimed at re-establishing its influence. On 24th March, 1996 China’s 150-member Preparatory Committee, which had been created to oversee the handover, voted to dissolve LEGCO and installed a provisional legislature after Hong Kong returned to Chinese sovereignty. In December 1996 a China-backed special election committee selected the 60 members of the provisional body, just days after it had overwhelmingly elected 59-year-old Tung Chee-hwa as the first Chief Executive of the HKSAR. Tung soon signalled his intention to roll back Patten’s reforms, announcing in April 1997 proposals to restrict political groups and public protests after the handover. After the handover, however, the situation in Hong Kong remained stable but complete freedom in the exercising political and civil rights remained doubtful.

In September 2002, Hong Kong government released a proposal to implement Article 23 of the Basic Law. In February 2003, the National Security (Legislative Provisions) Bill was introduced in the Legislative Council. This caused a massive upheaval in the city and the bill was finally withdrawn by the government following a huge protest by the citizens of Hong Kong on 1st July, 2003. The city has witnessed many protests since the British handing over of Hong Kong to China. Each protest has culminated into a “pro-democracy” protest. In 2012, Protests broke out in Hong Kong as the authorities tried to change the curriculum of the school system in Hong Kong. The 2014 Umbrella Movement was a movement against the decision of China’s National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC) regarding the ‘proposed reforms of the Hong Kong electoral system.’ The reforms suggested a pre-screening of the candidates by the CPC for the post of Chief Executive of Hong Kong. The 2016 protestwas the first pro-independence protest held in Hong Kong as it demanded complete independence of Hong Kong from Mainland China. In 2017, as Hong Kong celebrated two decades of handing over of Hong Kong to the Chinese control, the pro- Democracy protesters marched against China’s refusal to grant ‘genuine autonomy’ to Hong Kong and the erosion of ‘one country, two systems.’ In 2019, the city, during the Anti-Extradition Bill movement, witnessed the most violent protests since its handover, as police used brutal force to supress it. It garnered the attention of the world and led to massive criticism of China on the international stage.

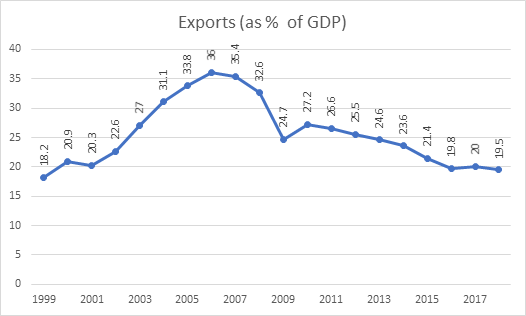

The Bill was eventually shelved indefinitely, causing major embarrassment for the CPC. Hong Kong was the last remains of the humiliation faced by China at the hands of a foreign power. Even when return to Chinese rule, in terms of politics, society and culture, there has been vast discrepancies between Hong Kong and Mainland. China, time and again has tried to interfere in the city’s day-to-day affairs in order to create more semblance between Hong Kong and Mainland. On the economic front, although, Hong Kong is just 2.7% of China’s but it remains a most favoured destination for FDI due to its financial and legal system. While international companies use Hong Kong as a launching pad to expand into mainland China. The bulk of foreign direct investment (FDI) in China continues to be channelled through the city. Although, recently Shenzhen surpassed Hong Kong in terms of GDP, Hong Kong still provided systems and frameworks which cannot be provided by Mainland Shanghai or Shenzhen. Most of China’s biggest firms, from state-owned Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (1398.HK), to private firms like Tencent Holdings (0700.HK), have listed in Hong Kong, often as a springboard to global expansion. Last year, Chinese companies raised $64.2 billion globally – almost a third of the worldwide total – via initial public offerings (IPOs), but just $19.7 billion of that came from listings in Shanghai or Shenzhen. Hong Kong has also been pivotal to China’s longer-term ambition to turn the RMB (Yuan 元) into a widely-used international currency, competing with the U.S. dollar.

Conclusion

The citizens of Hong Kong have often voiced their concern over the ‘Mainlandization’ of the city and the waning of ‘One Country, Two Systems”. The passing of the National Security Law has caused a great amount of anxiety among the citizens and was termed as a “Death Knell” for democracy in Hong Kong. Every year, 1st July commemorates the anniversary of the British handing over of Hong Kong to China and the citizens take out an annual march on this day. On 1st July, 2020 the day which commemorated the 23rd anniversary of British handing over of Hong Kong, the citizens marched into the streets while National Security Law was already put in place. The day witnessed the actual implementation of the Law when the protestors were arrested under the new Law on charges of “inciting sedition and terrorism”.

While China received massive criticism over subversion of freedom and rights of citizen of Hong Kong from various countries including the U.S. and UK, HKSAR Chief Executive Carrie Lam stated that “the National Security Legislation will help restore stability in Hong Kong, and protect the life and property, basic rights and freedoms of the overwhelming majority of residents” and will not cause any harm to freedom possessed by the citizens of Hong Kong. China lashed out at the U.S. and UK, stating that while these powers have a National Security Law in place, they are against China for doing something similar. China’s current domestic politics including rising nationalistic sentiments, of which territory occupies a great portion and Xi Jinping’s aggressive foreign and domestic policies have a major effect on the implementation of the law. Besides, the 2019 protests and fading CCP’s patience to deal with Hong Kong together has also played a great role in panning out of the new Law. The Chief Executive elections which was due in September was very crucial to the Law. The Hong Kong government on 31st Aug 2020 announced the postponement of elections by 1 year. While the reason cited by the government was the pandemic, the pro-democracy opposition remarked that this was an attempt to prevent their winning which, according to them, is inevitable in the face of massive dissatisfaction among the Hong Kong citizens.

Finally, the Law has also affected China’s relation’s with other countries, including the U.S and UK. While Sino-US relations have already been on a crossroad due to trade war and the outbreak of COVID-19, the implementation of National Security Law by China and retaliation by the State Department of the U.S., further deteriorated the relations. U.S. has massive investment in Hong Kong which includes over 1,300 companies and $82.5 million dollars as direct investment and the new Law have put into risk U.S. business interest as it will no longer be protected under British-style common law jurisdiction. Moreover, as American elections remain due in November 2020, Trump has hardened its stand on China. On the other hand, the Sino-British relations have been in its ‘golden era’ post- ‘Brexit’. As Hong Kong constitutes an important part of Sino-British relationship, the National Security Law, means much more for the UK than what it stands for the U.S. Thus, UK’s has been the most direct international response against the implementation of the law.

As it were, other countries’ reactions make it easy for China to blame foreign interference and play the nationalist card to go through with the plan of completely integrating territories under the roof of ‘One China’.