Wonchibeni Patton, Research Intern, ICS

Source: Getty Images

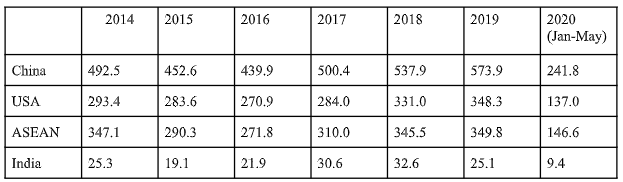

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is the third-largest aid donor to the Pacific Island Countries (PICs), spending around US$1.76 billion in aid towards the region. In its aid programme, the PRC emphasises on equality, mutual benefit and win-win cooperation. On this note, the following paragraphs examine the benefits that the PRC gains from its engagement with the PICs.

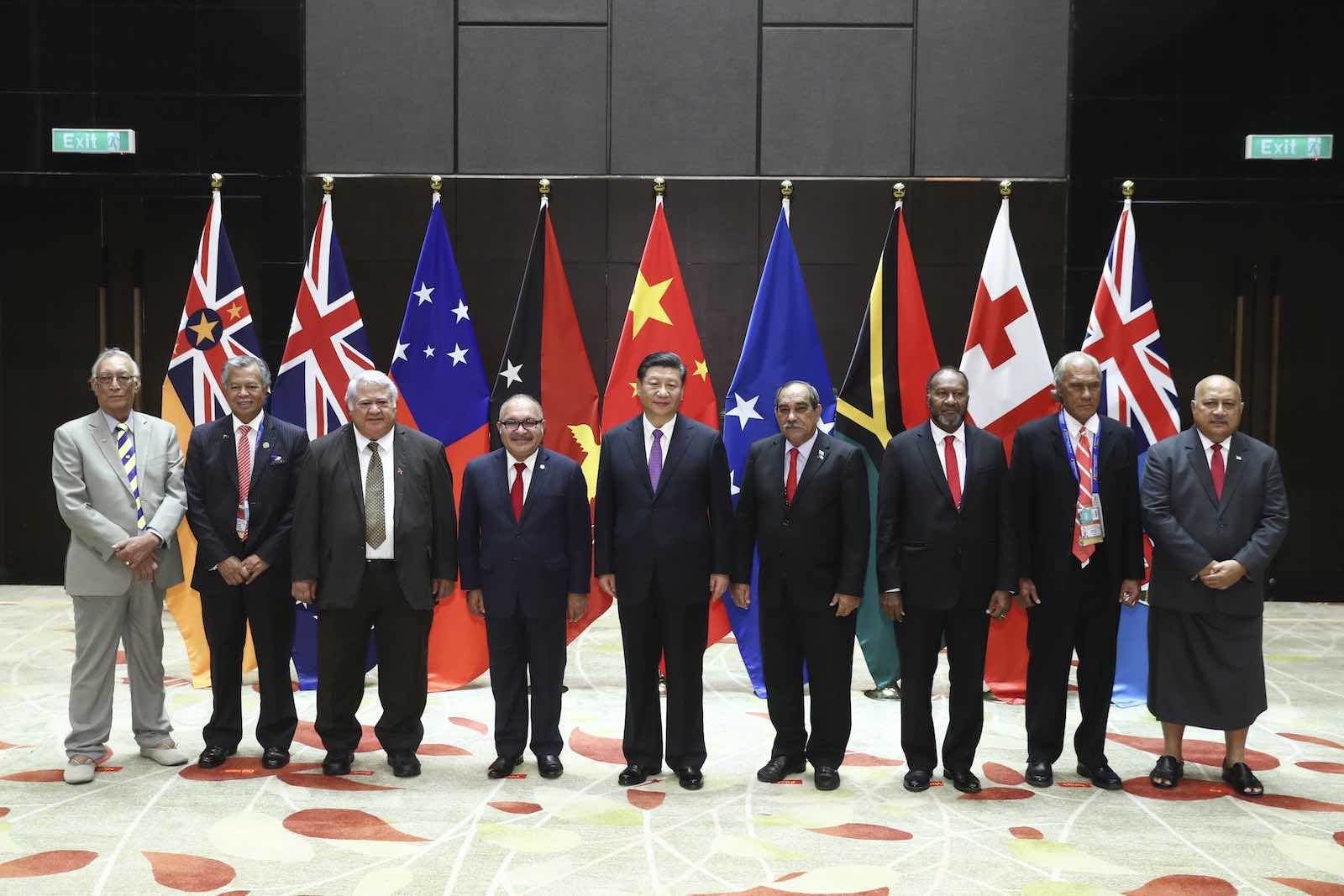

Scholars have identified the PRC’s two main interests in the PICs as political and economic. Political or diplomatic interests include decreasing Taiwan’s diplomatic clout and gaining the support of the PICs at multilateral forums, mainly the United Nations (UN). The PRC and Taiwan rigorously engaged in “chequebook diplomacy” in the 1990s, competing for diplomatic recognition from the PICs until 2008 when President Ma Ying-Jeou of the Kuomintang government came to power in Taiwan and led to a diplomatic truce. Before 2019, Taiwan had six diplomatic allies in the region, but this was reduced to four when the Solomon Islands, followed by Kiribati, switched to the PRC in September of 2019. There were several reports that the PRC had baited both countries with promised aid: US$500 million for the Solomon Islands and funds for aeroplanes and commercial ferries for Kiribati

Although the PICs occupy only 15 per cent of the world’s surface, with a cumulative population of around 13 million, they hold about 7 per cent of UN votes. The PRC’s membership in the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) has often been questioned, and the PRC is often targeted at the UN for its human rights record. The Xinjiang issue has been raised twice at the UNHRC in the recent past-2019 and 2021. Both were led by countries from the West. However, both times the PRC responded with greater support from its “Like-Minded Group”- a term used to describe a loose coalition of developing states often led by the PRC, Russia and Egypt . In 2020, when the issue of China’s new national security law in Hong Kong was raised at the 44th session of the UNHRC by 27 countries, Papua New Guinea was amongst the 53 countries that backed the PRC. In 2021, when the human rights situation in Xinjiang was raised at the 47th UNHRC session by Canada with the support of 44 countries, a coalition of 69 countries led by Belarus responded in China’s support. The PICs Kiribati, Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands were included in the 69. Thus, the PRC has been successful at garnering increasing support from the PICs on issues concerning its interests in international fora.

The PRC’s economic interests in the region include the promotion of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the hunt for raw materials. All the ten diplomatic partners of the PRC in the region have signed up for the BRI. The PICs’ total exclusive economic zones (EEZs) extend across nearly 7.7 million square miles of ocean. This can be beneficial to China’s endeavours in exploring and extracting natural resources. Some of the PICs are blessed with abundant natural resources and raw materials in terms of minerals, metals, fossil fuels, fisheries and wood. A global audit of Pacific resource extraction undertaken by the Guardian’s Pacific Project revealed that China is the largest importer of the region’s natural resources, importing resources worth US$3.3 billion in 2019. In the mining industry, the PRC has invested in seven mining projects across the region, with the largest one being the US$1.4 billion Ramu nickel and cobalt mine in PNG. PNG and Fiji have been the main focus of investments in this field. Other major operations include the Porgera gold mine and the Frieda River Copper project in PNG, the Nawailevu Bauxite mining project and the Vatukoula gold mine in Fiji, and so on. These operations are partly owned and run by Chinese SOEs such as Zijin Mining Group, Xinfa Aurum Exploration and Zhongrun International Mining. In 2019, PNG exported US$2.3 billion worth of oil, metals and minerals to China while Fiji exported US$4.8 million of the same.

The Pacific region is the world’s most fertile fishing ground. China imported US$100 million worth of seafood products from the region in 2019. However, Chinese vessels have also been involved in illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing, which has been threatening the region’s revenue sources and food security. Even though the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) states that China has around 600 licensed vessels fishing in the area, various estimates of the Chinese fleet range between 1,600 and 3,400 vessels. The major exporters of tropical logs in the region are PNG and Solomon Islands, where forestry is a major industry. According to the US Department of Agriculture report, in 2020, Papua New Guinea was the largest hardwood log exporter to China, accounting for 21 per cent of China’s total imports, followed by the Solomon Islands. The Pacific region’s emerging potential as the ‘blue economy’ has also caught Chinese interest. China has started looking into Deep Sea Mining by conducting research projects through the China Ocean Mineral Resources Research and Development Association (COMRA). They have identified polymetallic and cobalt nodules, hydrothermal sulfide deposits and have also produced several deep-sea mining maps in the Pacific. Furthermore, in 2017, China signed a 15-year exploration contract for polymetallic nodules in the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone in the Pacific Ocean with the International Seabed Authority. Although the gains from the Sino-Pacific engagement may not be equal in quantity, Sino-Pacific engagement can be considered a qualitative ‘win-win’. Certainly, China’s primary goals in the region are being met to some degree on both the political and economic fronts.