Mohd. Adnan, Research Intern, ICS

Contemporary

Sino-Japanese relations rested on the logic of economic competition and

interdependence along with prevalent distrusts and territorial disputes, have

become one of the most crucial bilateral relations in the world. Despite

competing with each other over various overlapping economic and strategic

interests, their increasing bilateral trade have inextricably bound to each

other. World’s second and third largest economy China and Japan respectively,

at one side, entangled in regional competition to gain influence and their confrontations

over disputed

Senkaku (Diaoyu) Islands situated in East China sea.

On the other side, their indispensable economic interdependence has been the

key aspect of their complex relationships. In 2012, the relations between them

were severely strained over the confrontations on Senkaku islands. However, increasing

economic interdependence and United States’ inward looking “America First”

approach have provided an impetus for both states to pacify their relations. This

paper intends to explore the contemporary dynamics of Sino-Japanese bilateral

relationship.

Historically,

Sino-Japanese relations have been of a competitive nature rather than mutual

collaboration. Japanese aggression during the late nineteenth and first half of

twentieth century has left a deep impact on contemporary Sino-Japanese relations.

The relations between them got normalized in the beginning of 1970s and

subsequently, they have signed the Treaty of Peace and Friendship in 1978.

Japan has invested heavily in and provided much needed essential technologies

to China for its development in the post-Mao era. As Kerry Brown in his 2016 article

in The Diplomat, explained,

without Japan’s assistance in form of ‘technology and knowledge’, China’s

opening up and reforms would not have succeeded ‘as quickly and extensively’ as

it happened.

The

end of the Cold War and relative rise of China created an environment of

competition between these two giants. In 2012, the relations between them hit

a serious blow when Japanese government

purchased three out of five Senkaku islands from their private owners in order to

fully legitimize its claim over the disputed islands. China vehemently opposed

this act and various anti-Japan protests erupted across mainland China.

Japanese products were boycotted by public and relations between them were

severely damaged.

The

impasse between China and Japan remained intact until a surge of populism was

witnessed in 2016 US presidential election. Consequently, the United States

partially relinquished its previous neoliberal approach of leading free trade

and open market and opted for an increasingly inward looking “America First”

approach. This so called “America First” approach allows the US administration to

renegotiate trade deals with its major trading partners and its adoption of

protectionist approach to pressurise these partners by putting tariffs. This

new development in the international market has unintentionally pushed China

and Japan to step aside their differences and come to a cooperative platform.

Amid US-China trade confrontation and its protectionist approach, first,

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang visited Tokyo and a subsequent reciprocal visit by

Japanese Prime Minister Shinjo Abe was witnessed in 2018. Since then both

states maintained their complicated relationships despite competing and

confronting with each other in many overlapping economic and strategic interests.

Contemporary

Sino-Japanese economic relations revolve around two sets of notion. On the one

hand, they are increasingly interdependent owing to the huge amounts of

bilateral trade. According to the data

provided by Japan’s foreign ministry in

fiscal year 2019, China is by far the largest trading partner of Japan and

bilateral trade between them well exceeds above US $ 300 billion. Further, China’s

vast demography and rising middle class provides a lucrative market to

export-led Japanese economy. While, witnessing the increasing rift between the

United States and China, Japan’s importance to China has grown in many ways.

Japan has been the major source of essential technology for China since its

‘opening up’ in late 1970s. At a time, when the US is barring

Chinese companies from acquiring essential technology, China’s reliance on

Japanese technology will only increase. Moreover, while the US is retaliating

against its major trade partners including China and Japan, increasing economic

engagement becomes a necessity for both states to reduce their dependence on the

US markets.

The

economic interdependence between China and Japan is expected to further

increase once the Regional Economic Comprehensive Partnership (RCEP) is signed.

RCEP

is a trade agreement, which emphasises on reducing tariffs, between the ten

member countries of Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), China,

Japan, India, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. Last year in November,

these states signed text-based negotiations, in which India opted to exclude

itself. However, a fissure

has surfaced in RCEP because Japan seems reluctant to sign the deal without the

inclusion of India. Japan fears without the involvement of India, RCEP will be

dominated by China. Though, China is coaxing both Japan and India to get back

in the fold of RCEP. It is expected that the Pact will be signed in the year

2020. According to a report

published in Xinhua on 5 November, 2019, “once

(RCEP) signed, it will form the largest free-trade agreement in Asia covering

47.4 percent of the world’s population, and accounting for 32.2 percent of

global GDP, 29.1 percent of trade worldwide and 32.5 percent of global

investment”.

On

the other hand, since both states are largely export-led economy, they have

been competing with each other in third party markets. China and Japan, in

recent years, increasingly competed

with each other in third party markets on trade, infrastructure projects, and

investments, particularly in Southeast Asian countries. Such is the competition

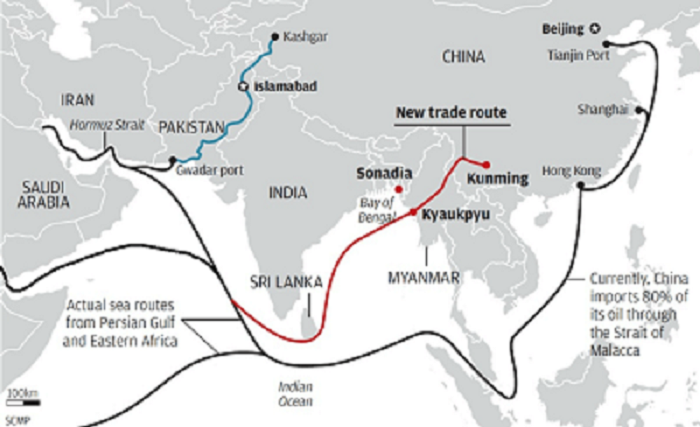

that Japan initially avoided to become part of China’s Belt and Road initiative

(BRI) – a land-based and maritime infrastructure projects aimed to enhance

China’s influence in and connectivity with the rest of Asia, Europe and Africa.

And in 2015, Japan initiated its own policy known as ‘Partnership

for Quality Infrastructure’ aimed to rival

BRI through developing infrastructure projects in foreign countries.

However,

in 2017, Japan agreed to cooperate with BRI under certain conditions. A year

later, on June 26, 2018, during the Japanese Prime Minister’s visit to Beijing,

the first ‘Third-Party Market Cooperation Forum’ was organised in which both

states agreed

to participate in conducting joint

venture projects in third-party markets. According to a report

published on the website of the State Council

of China on 26 October, 2018, ‘At the (aforementioned) forum, more than 50

cooperation agreements were reached between local governments, financial

institutions, and enterprises from the two sides, with the total amount

exceeding $ 18 billion’. But conducting such projects is fraught with difficulties,

given the competitive nature of this agreement and conditions placed by

Japanese government on its enterprises while venturing on third-party projects

with China. Further Japan’s insistence on quality and financial viability of

targeted projects contrasts with China’s ignorance of these elements. For

example, in 2018, a high

speed rail project in Thailand was planned

to be conducted by the companies from China and Japan but Japanese company

abandon this project due to the financial risks involved.

From

the strategic point of view, there has been a deep distrust and clash of

interests between China and Japan. China’s growing assertiveness in East and

South China seas and its claim over Senkaku (Diaoyu) islands and South China

Sea increasingly discomforts Tokyo. Further, China’s insistence to ignore

International Laws such as Permanent Courts

of Arbitration’s July 2016 decisions nullifying its claims in South China Sea

contrasts the principles and interests of Japan. To counter Chinese interests

and claims, in 2015, Japan introduced the vague concept of ‘Free and Open

Indo-Pacific’. Vague in the sense, it does not have a coherent policy and over

the years various elements have been added and removed. As the name indicates, it

promulgates for an open and free Indian and Pacific Ocean contrasts to China’s

claim over South China Sea and its growing influence in Indo-Pacific Ocean.

Apart from that, this vague policy also emphasises over freedom of navigation

and acceptance of international norms and laws.Through propagation of ‘Free and

Open Indo-Pacific’ approach, Japan seeks to mould China in the Western-led

International Laws and Treaties, and at the same time, Japan also wants to

constrain China’s assertiveness in the region detrimental to its interests.

Further,

China’s growing military power and its assertive nature in the region creates a

sense of insecurity in Japan. It is a common notion in Japan along with other regional

states that China seeks dominance and hegemony in Asian continent. To counter

it, Japan propagates a multi-polar order in Asia and adopted a policy of

building alliances with like-minded countries, which share the same views and

are worried with China’s relative rise. Japan has historical military

alliance with the US since the end of Second

World War. Recently these two states along with Australia and India have

revived the Quadrilateral

Security Dialogue initiative, which

earlier, in 2007, came into existence but faded away amid China’s opposition. Quad

initiative similar to ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ policy but differ in the

sense that it has four member state seeking to counter-check China’s growing

influence in the Asia-Pacific region.

Along

with the territorial dispute, Japan’s close association with the United States

and its opposition to Chinese assertiveness in the region have been contrary to

China’s interests. It is widely held belief in China that through the revival

of Quadrilateral strategic alliance, the US is trying to contain Chinese

influence in the region. Japan’s participation in this alliance is perceived by

China as a step to limit its growing influence in the region and taking side in

a broader Sino-US rivalry. In other words, China sees itself as a major power

capable of dominating Asian Continent and feasible challenger to the US led World

Order. It expects from Japan along with other regional actors to conform to its

interests and do not take side with the US in the broader Sino-US rivalry.

The

relations between China and Japan are one of the most complex bilateral

relations in the world. Despite competing and clashing with each other in

myriad of overlapping interests and prevalent distrust, their economy is well

integrated and bilateral trade have continuously been increasing. Their bilateral relations, which were severed

in 2012 over Japan’s nationalization of Senkaku (Diaoyu) islands, have been

steaming up again owing to relative decline of the US in the region and it’s

America First’ approach. Both states have been continuously propagating for

increasing engagement and cooperation. However, structural and political

differences between China and Japan remained intact as they were three years

ago before their rapprochement.